Arqa

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2013) |

Arqa

عرقا | |

|---|---|

City | |

Remains of Crusader Castle, Arqa | |

| Coordinates: 34°31′50″N 36°02′45″E / 34.53056°N 36.04583°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Akkar |

| District | Akkar |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Dialing code | +961 |

Arqa (Arabic: عرقا, romanized: ʿArqā; Akkadian: 𒅕𒋡𒋫, romanized: Irqata) is a Lebanese village[1] near Miniara in Akkar Governorate, Lebanon, 22 km northeast of Tripoli, near the coast.

The town was a notable city-state during the Iron Age. The city of Irqata sent 10,000 soldiers to the coalition against the Assyrian king in the Battle of Qarqar. The former bishopric became a double Catholic titular see (Latin and Maronite). The Roman Emperor Alexander Severus was born there. It is significant for the Tell Arqa, an archaeological site that goes back to Neolithic times, and during the Crusades there was a strategically significant castle.[2]

Names

[edit]It is mentioned in Antiquity in the Amarna letters of Egypt-(as Irqata), as well as in Assyrian documents.[3]

The Roman town was named Caesarea-ad-Libanum (of Lebanon/Phoenicia) or Arca Caesarea.[2]

History

[edit]Early Bronze

[edit]In the Early Bronze IV, the Akkar Plain had three major sites in Tell Arqa, Tell Kazel, and Tell Jamous.[4] The cultural focus had been towards the south and southern Levant, but now changed with more influence from Inner Syria and the use of copper.

Middle Bronze

[edit]In the MB I the Akkar Plain still saw smaller settlements being added near Tell Arqa and the region reach its highest population density in MB II.[5]

Late Bronze

[edit]Amarna Period Irqata (c. 1350 BC)

[edit]Arqa has the distinction of being a city-state that wrote one of the 382 Amarna letters to the Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt.[6]

The city-state Irqata was the 3rd city of the Rib-Hadda letters, (68 letters), that were the last hold-outs against the (H)Apiru invasion. Sumur(u)-(Zemar) was the 2nd hold-out city besides Rib-Hadda's Byblos, (named Gubla).[7] Eventually, the king of Irqata, Aduna was killed along with other city kings, and also the 'mayor' of Gubla, Rib-Hadda. Rib-Hadda's brother, Ili-Rapih, became the successor mayor of Gubla, and Gubla never fell to the Hapiru.

During Rib-Hadda's lengthy opposition to the Habiru, even the city-state of Irqata and its elders, wrote to the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten for assistance. (EA 100, EA for el Amarna).

The letter is entitled: "The city of Irqata to the king".

- This tablet-(i.e. tablet letter) is a tablet from Irqata. To the King, our Lord: Message from Irqata and its el[d]ers. We fall at the feet of the king, our lord, 7 times and 7 times. To our lord, the Sun: Message from Irqata. May the heart of the king, (our) lord, know that we guard Irqata for him.

- When the [ki]ng, our lord, sent D[UMU]-Bi-ha-a, he said to [u]s, "Message of the king: "Guard Irqata"! " The sons of the traitor to the king seek our harm; Irqata see[ks] loyalty to the king. As to [ silver ] having been given to S[u]baru al[ong with] horses and cha[riots] , may you know the mind of Irqata. When a tablet from the king arrived (saying) to ra[id] the land that the 'A[piru] had taken [from] the king,'they wa[ged] war with us against the enemy of our lord, the man whom you pla[ced] over us. Truly—we are guarding the l[and]. May the king, our lord, heed the words of his loyal servants.

- May he grant a gift to his servant(s) so our enemies will see this and eat dirt. May the breath of the king not depart from us. We shall keep the city gate barred until the breath of the king reaches us. Severe is the war against us—terribly! terribly! -EA 100, lines 1-44 (complete)[8][9]

Hellenistic and Roman period

[edit]

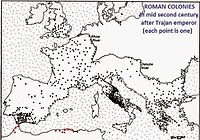

After the death of Alexander the Great Arca came under the control first of the Lagids then of the Seleucids. When the Romans gained control over this part of western Asia, they entrusted Arca as a client tetrarchy or vassal principality to a certain Sohaimos, who died in AD 48 or 49. It was then incorporated in the Roman province of Syria, but was soon entrusted to Herod Agrippa II. Pliny the Elder counts it among the tetrarchies of Syria. It was at this time that its name was changed to Caesarea,[10] distinguished from other cities of that name by being called Caesarea ad Libanum or Arca Caesarea. Under Septimius Severus (193–211) it was made part of the province of Syria Phoenicia and so became known as Arca in Phoenicia. Under his son Caracalla (198–217) it became a colonia and in 208 Alexander Severus was born at Arca during a stay of his parents there.[11]

Crusades period

[edit]At the time of the First Crusade, Arca became an important strategic point of control over the roads from Tripoli to Tartus and Homs. Raymond of Toulouse unsuccessfully besieged it for three months in 1099. In 1108, his nephew William II Jordan conquered it and it became part of the County of Tripoli. It resisted an attack by Nur ad-Din, atabeg of Aleppo, in 1167 and another in 1171.

It finally fell to Muslim forces of the Sultan Baibars in 1265 or 1266. When Tripoli itself fell in 1289 to the army of Sultan Qalawun and was razed to the ground, Arca lost its strategic importance and thereafter is mentioned only in ecclesiastical chronicles.[12]

Later period

[edit]In 1838, Eli Smith noted the village, whose inhabitants were Greek Orthodox, located west of esh-Sheikh Mohammed.[13]

Ecclesiastical history

[edit]Arca in Phoenicia became the seat of a Christian bishop in the Roman province of Phoenicia Prima, a suffragan of the capital's metropolitan see of Tyre.

Of its bishops, Lucianus professed the faith of the First Council of Nicaea at a synod held in Antioch in 363, Alexander was at the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Reverentius became archbishop of Tyre, Marcellinus was a participant at the Council of Ephesus in 431, Epiphanius took part in a synod at Antioch in 448, and Heraclitus participated in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and was a signatory of the letter that the bishops of the province of Syria Phoenicia sent in 458 to Byzantine Emperor Leo I the Thracian to protest about the murder of Proterius of Alexandria.[14][15][16]

No longer a residential bishopric, Arca in Phoenicia is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see,[17] in two traditions: Latin and Maronite (Eastern Catholic, Antiochian Rite in Syriac).

Latin titular see

[edit]The nominally restored diocese has had non-consecutive titular bishops as a Latin Catholic titular bishopric since the 18th century.

It is vacant, having had the following incumbents, all of the lowest (episcopal) rank :

- Pedro del Cañizo Losa y Valera (1726.09.21 – ?)

- Józef Krystofowicz (1809.03.28 – 1816.02.26)

- Francisco de Sales Crespo y Bautista (1861.12.23 – 1875.07.05)

- Pierre-Marie Le Berre, Holy Ghost Fathers (C.S.Sp.) (1877.09.07 – 1891.07.16)

- Claude Marie Dubuis (1892.12.16 – 1895.05.22)

- Alfredo Peri-Morosini (1904.03.28 – 1931.07.27)

- Jean-Édouard-Lucien Rupp (1954.10.28 – 1962.06.09) as Auxiliary Bishop of France of the Eastern Rite (France) (1954.10.28 – 1962.06.09), later Exempt Bishop of the then diocese of Monaco (Monaco) (1962.06.09 – 1971.05.08), Apostolic Pro-Nuncio (papal diplomatic envoy) to Iraq (1971.05.08 – 1978); later Titular Archbishop of Dionysiopolis (1971.05.08 – 1983.01.28), Apostolic Pro-Nuncio to Kuwait (1975 – 1978), Permanent Observer to Office of the United Nations and Specialized Institutions in Geneva (UNOG) (1978 – 1980)

- Hugo Aufderbeck (1962.06.19 – 1981.01.17)

Maronite titular see

[edit]Established as Titular Episcopal See of Arca (Arca dei Maroniti in Curiate Italian); promoted in 1933 as Titular Archiepiscopal See of Arca in Armenia, in 1941 suppressed, but restored in 1950 as Titular Episcopal See of Arca in Phoenicia.

It has had the following incumbents, all of the lowest (episcopal) rank :

- Abdallah Nujaim (1950.07.25 – 1954.04.04)

- Bishop-elect João Chedid, Mariamite Maronite Order (O.M.M., Aleppians) (1956.05.04 – 1956.05.04), as Auxiliary Bishop of Brazil of the Eastern Rite (Brazil) ([1956.04.21] 1956.05.04 – 1971.11.29), later Bishop of Nossa Senhora do Líbano em São Paulo of the Maronites (Brazil) (1971.11.29 – 1988.02.27), Archbishop-Bishop of Nossa Senhora do Líbano em São Paulo of the Maronites (1988.02.27 – 1990.06.09)

- Roland Aboujaoudé (1975.07.12 – ...), Auxiliary Bishop emeritus of Antioch of the Maronites (Lebanon)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Municipal and ikhtiyariah elections in Northern Lebanon" (PDF). The Monthly. March 2010. p. 22. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "Tourism @ Lebanon.com". www.lebanon.com. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ karim.sokhn (2023-04-29). "Arqa Site". wanderleb. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ Thalmann 2007:221

- ^ Thalmann 2007:221

- ^ "Tal Arqa, a great city in Antiquity - LebanonUntravelled.com". 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ "The Amarna Letters; Rib-addi of Byblos | Ancient Egypt Online". Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ Pryke, Louise M. (2011). "The Many Complaints to Pharaoh of Rib-Addi of Byblos". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 131 (3): 411–422. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 41380709.

- ^ Moran, William (1992). The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press. doi:10.56021/9780801842511. ISBN 978-0-8018-4251-1.

- ^ The Middle East under Rome, Maurice Sartre (Harvard University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-67401683-5), p. 77

- ^ S.M. Cecchini, "Tell'Arqa" in Enciclopedia dell'Arte Antica (Treccani 1997)

- ^ "Tal Arqa, a great city in Antiquity - LebanonUntravelled.com". 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 183

- ^ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 823-826

- ^ Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 7, p. 86

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 434

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 837

Bibliography

[edit]- Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987, 1992. (softcover, ISBN 0-8018-6715-0)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Jean-Paul Thalmann (2007) Agricultural practices and settlement patterns in the Akkar plain (Northern Lebanon) in the Late Early and Early Middle Bronze Ages. Pp. 219-232 in : MORANDI-BONACOSSI, D. (ed) Urban and Natural Landscapes of an Ancient Syrian Capital