Classical architecture

Classical architecture usually denotes architecture which is more or less consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or sometimes more specifically, from De architectura (c. 10 AD) by the Roman architect Vitruvius.[1][2] Different styles of classical architecture have arguably existed since the Carolingian Renaissance,[3] and prominently since the Italian Renaissance. Although classical styles of architecture can vary greatly, they can in general all be said to draw on a common "vocabulary" of decorative and constructive elements.[4][5][6] In much of the Western world, different classical architectural styles have dominated the history of architecture from the Renaissance until World War II. Classical architecture continues to inform many architects.

The term classical architecture also applies to any mode of architecture that has evolved to a highly refined state, such as classical Chinese architecture, or classical Mayan architecture. It can also refer to any architecture that employs classical aesthetic philosophy. The term might be used differently from "traditional" or "vernacular architecture" although it can share underlying axioms with it.

For contemporary buildings following authentic classical principles, the term New Classical architecture is sometimes used.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Classical architecture is derived from the architecture of ancient Greece and ancient Rome. With the collapse of the western part of the Roman empire, the architectural traditions of the Roman empire ceased to be practised in large parts of western Europe. In the Byzantine Empire, the ancient ways of building lived on but relatively soon developed into a distinct Byzantine style.[7] The first conscious efforts to bring back the disused language of form of classical antiquity into Western architecture can be traced to the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and 9th centuries. The gatehouse of Lorsch Abbey (c. 800), in present-day Germany thus displays a system of alternating attached columns and arches which could be an almost direct paraphrase of e.g., that of the Colosseum in Rome.[8] Byzantine architecture, just as Romanesque and even to some extent Gothic architecture (with which classical architecture is often posed), can also incorporate classical elements and details but do not to the same degree reflect a conscious effort to draw upon the architectural traditions of antiquity; for example, they do not observe the idea of a systematic order of proportions for columns. In general, therefore, they are not considered classical architectural styles in a strict sense.[9]

Development

[edit]

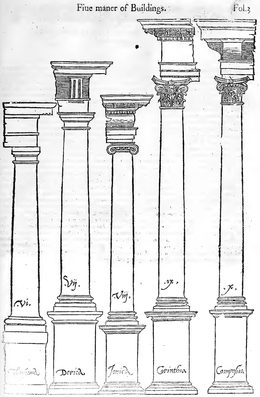

During the Italian Renaissance and with the demise of Gothic style, major efforts were made by architects such as Leon Battista Alberti, Sebastiano Serlio and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola to revive the language of architecture of first and foremost ancient Rome. This was done in part through the study of the ancient Roman architectural treatise De architectura by Vitruvius, and to some extent by studying the actual remains of ancient Roman buildings in Italy.[10] Nonetheless, the classical architecture of the Renaissance from the outset represents a highly specific interpretation of the classical ideas. In a building like the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence by Filippo Brunelleschi, one of the earliest Renaissance buildings (built 1419–1445), the treatment of the columns for example has no direct antecedent in ancient Roman architecture.[11] During this time period, the study of ancient architecture developed into the architectural theory of classical architecture; somewhat over-simplified, that classical architecture in its variety of forms ever since have been interpretations and elaborations of the architectural rules set down during antiquity.[12]

Most of the styles originating in post-Renaissance Europe can be described as classical architecture. This broad use of the term is employed by Sir John Summerson in The Classical Language of Architecture. The elements of classical architecture have been applied in radically different architectural contexts than those for which they were developed, however. For example, Baroque or Rococo architecture are styles which, although classical at root, display an architectural language much in their own right. During these periods, architectural theory still referred to classical ideas but rather less sincerely than during the Renaissance.[13]

The Palladian architecture developed from the style of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) had a great influence long after his death, above all in Britain, where it was adopted for many of the grander buildings of the Georgian architecture of the 18th and early 19th century.

As a reaction to late Baroque and Rococo forms, architectural theorists from c. 1750 through what became known as Neoclassicism again consciously and earnestly attempted to emulate antiquity, supported by recent developments in Classical archaeology and a desire for an architecture based on clear rules and rationality. Claude Perrault, Marc-Antoine Laugier and Carlo Lodoli were among the first theorists of Neoclassicism, while Étienne-Louis Boullée, Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Friedrich Gilly and John Soane were among the more radical and influential.[13] Neoclassical architecture held a particularly strong position on the architectural scene c. 1750–1850. The competing neo-Gothic style however rose to popularity during the early 1800s, and the later part the 19th century was characterised by a variety of styles, some of them only slightly or not at all related to classicism (such as Art Nouveau), and Eclecticism. Although classical architecture continued to play an important role and for periods of time at least locally dominated the architectural scene, as exemplified by the Nordic Classicism during the 1920s, classical architecture in its stricter form never regained its former dominance. With the advent of Modernism during the early 20th century, classical architecture arguably almost ceased to be practised.[14]

Scope

[edit]

As noted above, classical styles of architecture dominated Western architecture for a long time, roughly from the Renaissance until the advent of Modernism. That is to say, that classical antiquity at least in theory was considered the prime source of inspiration for architectural endeavours in the West for much of Modern history. Even so, because of liberal, personal or theoretically diverse interpretations of the antique heritage, classicism covers a broad range of styles, some even so to speak cross-referencing, like Neo-Palladian architecture, which draws its inspiration from the works of Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who himself drew inspiration from ancient Roman architecture.[15] Furthermore, it can be argued that styles of architecture not typically considered classical, like Gothic, can contain classical elements. Therefore, a simple delineation of the scope of classical architecture is difficult to make.[16] The more or less defining characteristic can still be said to be a reference to ancient Greek or Roman architecture, and the architectural rules or theories that derived from that architecture.

Petrification

[edit]

In the grammar of architecture, the word petrification is often used when discussing the development of sacred structures such as temples, mainly with reference to developments in the Greek world. During the Archaic and early Classical periods (about the 6th and early 5th centuries BC), the architectural forms of the earliest temples had solidified and the Doric emerged as the predominant element. The most widely accepted theory in classical studies is that the earliest temple structures were of wood and the great forms, or elements of architectural style, were codified and rather permanent by the time the Archaic became emergent and established. It was during this period, at different times and places in the Greek world, that the use of dressed and polished stone replaced the wood in these early temples, but the forms and shapes of the old wooden styles were retained in a skeuomorphic fashion, just as if the wooden structures had turned to stone, thus the designation "petrification"[17] or sometimes "petrified carpentry"[18] for this process.

This careful preservation of the traditional wooden appearance in the stone fabric of the newer buildings was scrupulously observed and this suggests that it may have been dictated by religion rather than aesthetics, although the exact reasons are now lost in antiquity. Not everyone within the reach of Hellenic civilization made this transition. The Etruscans in Italy were, from their earliest period, greatly influenced by their contact with Greek culture and religion, but they retained their wooden temples (with some exceptions) until their culture was completely absorbed into the Roman world, with the great wooden Temple of Jupiter on the Capitol in Rome itself being a good example. Nor was it the lack of knowledge of stone working on their part that prevented them from making the transition from timber to dressed stone.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Neoclassical architecture

- New Classical architecture

- Outline of classical architecture

- Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

References

[edit]- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1986). Dictionary of architecture (3 ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 0-14-051013-3.

- ^ Watkin, David (2005). A History of Western Architecture (4th ed.). Watson-Guptill Publications. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-8230-2277-3.

- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1986). Dictionary of architecture (3rd ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 0-14-051013-3.

- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1986). Dictionary of architecture (3rd ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 0-14-051013-3.

- ^ Watkin, David (2005). A History of Western Architecture (4 ed.). Watson-Guptill Publications. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-8230-2277-3.

- ^ Summerson, John (1980). The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-500-20177-3.

- ^ Adam, Robert (1992). Classical Architecture. Viking. p. 16.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1964). An Outline of European Architecture (7 ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 45–47.

- ^ Summerson, John (1980). The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-500-20177-3.

- ^ Summerson, John (1980). The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-500-20177-3.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1964). An Outline of European Architecture (7th ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 177–178.

- ^ Evers, Bernd; Thoenes, Christof (2011). Architectural Theory from the Renaissance to the Present. Vol. 1. Taschen. pp. 6–19. ISBN 978-3-8365-3198-6.

- ^ a b Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1986). Dictionary of architecture (3rd ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 0-14-051013-3.

- ^ Summerson, John (1980). The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd. p. 114. ISBN 0-500-20177-3.

- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1986). Dictionary of architecture (3rd ed.). Penguin Books Ltd. p. 234. ISBN 0-14-051013-3.

- ^ Summerson, John (1980). The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-500-20177-3.

- ^ Gagarin, Michael. The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Oxford [u.a.: Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 210. ISBN 0195170725

- ^ Watkin, David. A history of Western architecture. 4th ed. London: Laurence King, 2005. p. 25. ISBN 1856694593

Further reading

[edit]- Sir John Summerson (rev. 1980) The Classical Language of Architecture ISBN 978-0-500-20177-0.

- Gromort Georges (Author), Richard Sammons (Introductory Essay). The Elements of Classical Architecture (Classical America Series in Art and Architecture), 2001, ISBN 0-393-73051-4.

- OpenSource Classicism – project for free educational content about classical architecture (video on YouTube)

- The Foundations of Classical Architecture Part Two: Greek Classicism – free educational program by the ICAA (published August 29, 2018)