Meiobenthos

| Part of a series related to |

| Benthic life |

|---|

|

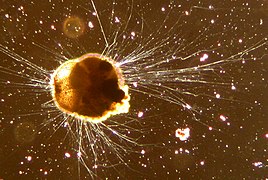

Meiobenthos, also called meiofauna, are small benthic invertebrates that live in marine or freshwater environments, or both. The term meiofauna loosely defines a group of organisms by their size—larger than microfauna but smaller than macrofauna—rather than by their taxonomy. This fauna includes both animals that turn into macrofauna later in life, and those small enough to belong to the meiobenthos their entire life. In marine environments there can be thousands of individuals in 10 cubic centimeters of sediment, and counts animals like nematodes, copepods, rotifers, tardigrades and ostracods, but protists like ciliates and foraminifers within the size range of the meiobethos are also often included. In practice, the term usually includes organisms that can pass through a 1 mm mesh but are retained by a 45 μm mesh, though exact dimensions may vary.[1] Whether an organism will pass through a 1 mm mesh also depends upon whether it is alive or dead at the time of sorting.

The term meiobenthos was first coined in 1942 by marine biologist Molly Mare, but organisms that fit into the modern meiofauna category have been studied since the 18th century.

Meiofaunal taxa

[edit]| Meiofaunal taxa based on the scheme of Nielsen (2001) |

|---|

| meiofaunal taxa shown in bold |

|

Collecting the meiobenthos

[edit]

Meiofauna are most commonly encountered in sedimentary environments in both marine and freshwater environments, from the littoral to the deep-sea. They can also be found on hard substrates living on algae, the phytal environment, and sessile animals (barnacles, mussel beds, etc.).

Sampling methodologies

[edit]Sampling the meiobenthos is dependent upon the environment and whether quantitative or qualitative samples are required. In the sedimentary environment, the methodology used also depends on the physical morphology of the sediment. For qualititative sampling within the littoral zone, for both coarse and fine sediment, a bucket and spade will work. In the sub-littoral and deep water, some form of grab (like the Van Veen grab sampler) is required, although a fine mesh (about 0.25 mm or less) would work also.

For the quantitative sampling of sedimentary environments at all depths, a wide variety of samplers have been devised. The simplest is a plastic syringe with the end cut off to form a piston corer which can be deployed in the littoral zone, or in the sub-littoral using SCUBA gear. Generally the deeper the water, the more complicated the sampling process becomes. For sampling the meiofauna on hard substrates or phytal or epizootic environments, the only practical methodology is to cut or scrape off a known area of the substrate and place it in a plastic bag.

Extraction methodologies

[edit]There are a wide variety of methods for extracting meiofauna from the samples of their habitat depending upon whether live or fixed specimens are required. For extracting live meiofauna, one has to contend with the large number of species that cling or attach themselves to the substrate when disturbed. In order to get the meiofauna to release their grip, there are three methodologies available.

The first, and simplest, is osmotic shock, which is achieved by submerging the sample in fresh water for a few seconds (this only works for marine samples). This will cause the organisms to release, after which they can be shaken free from the substrate and filtered out through a 45 μm mesh and immediately returned to fresh filtered seawater. Many organisms will come through this process unharmed as long as the osmotic shock does not last too long.

The second methodology is the use of an anaesthetic. The preferred chemical solution for meiobenthologists is isotonic magnesium chloride (7.5g MgCl2·6H2O per 100 mL of distilled water). The sample is immersed in the isotonic solution and left for a period of 15 min, after which the meiofauna are shaken free of the substrate and again filtered out through a 45 μm mesh and immediately returned to fresh filtered seawater.

The third methodology is Uhlig's seawater ice technique.[2] This relies on the organisms moving ahead of a front of ice-cold seawater moving down through the sample, ultimately forcing them out of the sediment. It is most effective on samples from temperate and tropical regions.

For major studies where large numbers of samples are collected concurrently, samples are normally fixed using a 10% formalin solution, and the meiofauna are extracted at a later date. There are two main extraction methodologies. The first, decantation, works best with coarse sediments. Samples are shaken in an excess of water, the sediment is briefly allowed to settle, and then the meiofauna are filtered off. The second methodology, the flotation technique, works best with finer sediments, where the mass of the sediment particles is close to that of the meiofauna. The best solution for this technique is the colloidal silica Ludox. The sample is stirred into the Ludox solution and left to settle for 40 min, after which the meiofauna are filtered out. In fine sediments, extraction efficiency is improved with centrifugation. With both methodologies, repeated extractions should be made (at least three) with each sample to ensure that at least 95% of the meiofauna is extracted.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sedimentary Coastal Zones from High to Low Latitudes: Similarities and Differences

- ^ Uhlig, G.; Thiel, H.; Gray, J. S. (1973-05-01). "The quantitative separation of meiofauna". Helgoländer wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen. 25 (1): 173–195. Bibcode:1973HWM....25..173U. doi:10.1007/BF01609968. ISSN 1438-3888. S2CID 46016793.

- Giere, Olav (2009). Meiobenthology: The microscopic motile fauna of aquatic sediments, 2nd edition, Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68657-6.

- Higgins, R.P. and Thiel, H. (1988). Introduction to the study of meiofauna. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. ISBN 0-87474-488-1

- Mare, M.F. (1942). A study of a marine benthic community with special reference to the micro-organisms. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 25:517-554.

- Nielsen, C. (2001). Animal evolution: Interrelationships of the living phyla. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850682-1

- Uhlig, G., Thiel, H. and Gray, J.S. (1973). The quantitative separation of meiofauna. Helgoländer wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen, 11: 178–185.