Cuyahoga Valley National Park

| Cuyahoga Valley National Park | |

|---|---|

Waterfalls, such as this one, can be found throughout the park | |

| Location | Summit County & Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States |

| Nearest city | Cleveland, Akron |

| Coordinates | 41°14′30″N 81°32′59″W / 41.24167°N 81.54972°W |

| Area | 32,783 acres (51.2 sq mi; 132.7 km2)[1] |

| Established | October 11, 2000 |

| Visitors | 2,860,059 (in 2023)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | nps |

Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a national park of the United States in Ohio that preserves and reclaims the rural landscape along the Cuyahoga River between Akron and Cleveland in Northeast Ohio.

The 32,783-acre (51.2 sq mi; 132.7 km2) park[1] is administered by the National Park Service, but within its boundaries are areas independently managed as county parks or as public or private businesses. Cuyahoga Valley was originally designated as a national recreation area (NRA) in 1974, then redesignated as a national park 26 years later in 2000, and remains the only national park that originated as a national recreation area.

Cuyahoga Valley is the only national park in the state of Ohio and one of three in the Great Lakes Basin, with Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior and Indiana Dunes National Park bordering Lake Michigan. Cuyahoga Valley also differs from the other national parks in the US in that it is adjacent to two large urban areas and it includes a dense road network, small towns, four reservations of the Cleveland Metroparks, four parks and one multipurpose trail of Summit Metro Parks, and public and private attractions. It was the twelfth-most visited American national park in 2023, attracting nearly 2.9 million visitors.[3]

History

[edit]

Indigenous history

[edit]The Hopewell Culture inhabited the area by ~200AD and constructed the Everett Mound near Everett within the park.[4]

No Native American tribes currently have federal recognition in Ohio;[5] however, the former inhabitants of the Cuyahoga Valley were Native Americans.[6] The Wyandot, Iroquois, Ottawa, Ojibwe, Munsee, Potawatomi, Miami, Catawba, and Shawnee all lived in or traversed this area, but the Lenapé Nation, also known as the Lenape’wàk or Delaware Nation, are considered "the Grandfathers" of many Native Nations of the upper Ohio River Valley.[7][8] They had a democratic and egalitarian sociopolitical structure where leaders (sachem) consulted elders who advocated for the expectations of the people before decisions were made.[9] The Lenapé were actively involved in long-distance trade networks and were highly skilled at creating goods and art such as pottery, stone weaponry, clothing, and baskets.[9] Wars, coercive treaties, and legislative changes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries resulted in Lenapé movement both west and south from their geographic origins in present-day New York City, the lower Hudson Valley, eastern Pennsylvania,[10] New Jersey,[11] and northern Delaware,[12] through the Ohio River Valley and Cuyahoga Valley, to current residencies primarily in Oklahoma and Ontario, Canada.[13][14]

Land was vitally important to the Lenapé Nation. The fur trade required large hunting grounds, as did agriculture, which served as their central food source.[14] As the Lenapé Nation was pushed west, ecological consistencies between present-day Pennsylvania and Ohio allowed them to continue similar agricultural, hunting, and fishing practices; however, as treaties and violent conflicts continued, the Lenapé were not permitted sufficient time to develop a relationship with land in the Ohio River Valley.[15] While being pushed west, the Lenapé turned to each other to form alliances between Lenapé communities to preserve culture, territory, and resources.[16]

The Lenapé’s hunting practices changed with the introduction of the fur trade.[6][17] After contact with Europeans, the emphasis on hunting began to shift towards the demands of fur production rather than prioritizing sustainability.[6] Because of this shift in Lenapé hunting practices, the populations of beavers and other fur-bearing animals plummeted.[18] These trade networks depended on waterways used by indigenous people through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries:

Portage Path was located in modern-day Summit County, Ohio. The trail connected the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas Rivers and was approximately eight miles in length. American Indians used this path to transport their canoes overland from one river to the other. Using canoes, American Indians could travel by water from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico except for this small section. Today, most of the path is located in the city of Akron, Ohio, although interested parties can follow signs that trace the path between the two rivers. Portage County received its name from Portage Path.[19]

Treaties and conflict

[edit]

The Cuyahoga Valley is no longer inhabited by the Lenapé Nation primarily due to coercive legislative processes and numerous violent conflicts.[20] The 1795 Treaty of Greenville set the Cuyahoga River as the boundary between indigenous peoples' lands and European settlement. In 1805, 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of land, including the present-day Cuyahoga Valley National Park, was ceded in the Treaty of Fort Industry with a promise of a thousand dollar annual payout to each Native Nation that lost land (the Wyandot, Ottawa, Objibwe, Munsee, Lenapé, Potawatomi, and Shawnee).[21] The treaty also included a clause that allowed for the continuation of indigenous hunting on the ceded land; however, that portion of the treaty was neglected in practice. Other treaties, also took Lenapé land without their full knowledge or consent.[22] Today, the Lenapé Nation is more commonly referred to as the Delaware Nation and has its headquarters in Oklahoma, although there are also populations in Kansas, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada,[23][24][25] as well as in their ancestral homelands, including Pennsylvania,[10] New Jersey,[11] and Delaware.[12]

Later history

[edit]The valley began providing recreation for urban dwellers in the 1870s when people came from nearby cities for carriage rides or leisure boat trips along the canal. In 1880, the Valley Railway became another way to escape urban industrial life. Actual park development began in the 1910s and 1920s with the establishment of Cleveland and Akron metropolitan park districts. In 1929, the estate of Cleveland businessman Hayward Kendall donated 430 acres (0.7 sq mi; 1.7 km2) around the Ritchie Ledges[26] and a trust fund to the state of Ohio. Kendall's will stipulated that the "property should be perpetually used for park purposes". The area was called Virginia Kendall Park, in honor of his mother. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built much of the park's infrastructure including the Happy Days Lodge and the shelters at Octagon, the Ledges, and Kendall Lake.[27] The Happy Days Lodge, near Peninsula, was constructed from 1938 to 1939 as a camp for urban children.[28] The lodge is presently used only as a special events site.[29]

Park creation

[edit]Although the regional parks safeguarded certain places, by the 1960s local citizens feared that urban sprawl would overwhelm the Cuyahoga Valley's natural beauty. An additional concern was the environmental degradation of the Cuyahoga River via factory waste and sewage, along with fires that burned on the river in 1952 and 1969.[30][31] Citizens joined forces with state and national government staff to find a long-term solution. Finally, on December 27, 1974, President Gerald Ford signed the bill establishing the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area,[32] even as the administration recommended a veto because "The Cuyahoga Valley possesses no qualities which qualify it for inclusion in the National Park System" and the government was already providing funds for outdoor recreation.[33]

After Congress authorized the land acquisition, it was left under the direction of Superintendent William C. Birdsell of the National Park Service and the Army Corps of Engineers .[34] Under the direction of Birdsell, homes were either purchased outright, or given a scenic/preservation easement. There was no comprehensive plan to guide the land acquisition program, so the responsibility of choosing whether homes were to be purchased or preserved was solely Birdsell's decision. Birdsell's continually changing priorities frustrated local residents as land acquisition plans changed,[35] and his management style was criticized by the National Park Service's Midwest Regional Office during a 1978 operational evaluation report (OER), citing his poor human-resource management skills, low staff morale, and Birdsell's inability to delegate.[36]

National Park Service

[edit]The National Park Service acquired the 47-acre (0.1 sq mi; 0.2 km2) Krejci Dump in 1985 to include as part of the recreation area. They requested a thorough analysis of the site's contents from the Environmental Protection Agency. After the survey identified extremely toxic materials, the area was closed in 1986 and designated a superfund site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980.[37] Litigation was filed against potentially responsible parties: Ford, General Motors, Chrysler, 3M, Waste Management, Chevron, Kewanee Industries, and Federal Metals.[38] Only 3M would not agree to a settlement, and the company lost at trial.[39] Removal of toxic materials began in 1987 with 371,000 short tons (740 million lb; 337 million kg) of contaminated soils and debris removed by 2012, and restoration completed by 2015.[37][40]

The area was redesignated a national park by Congress on October 11, 2000,[32] with the passage of the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2001, House Bill 4578, 106th Congress.[41][42] The park is administered by the National Park Service. The David Berger National Memorial in Beachwood, a Cleveland suburb, is also managed through Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

The Richfield Coliseum, a multipurpose arena in the Cuyahoga River area, was demolished in 1999 and the vacant site became part of Cuyahoga Valley National Park upon its designation in 2000. The area has since become a grassy meadow that is a popular birdwatching site.[43][44]

In 2024, Cuyahoga Valley National Park entered into a "sister park" agreement with Dartmoor National Park in Devon, England, with a focus on collaborating to improve conservation efforts. The agreement is the first of its kind between the National Park Service and an English national park.[45]

Wildlife

[edit]Animals found in the park include raccoons, muskrats, coyotes, skunks, red foxes, beavers, peregrine falcons, river otters, bald eagles, opossums, three species of moles, white-tailed deer, Canada geese, gray foxes, minks, great blue herons, and seven species of bats.[46]

Climate

[edit]The Boston Mill Visitor Center at Cuyahoga Valley National Park has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa). The plant hardiness zone at Boston Store Visitor Center is 6a with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of −6.5 °F (−21.4 °C).[47]

| Climate data for Boston Mill Visitor Center, elevation 722 ft (220 m), 1981-2010 normals, extremes 1981-2019 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69.3 (20.7) |

75.7 (24.3) |

82.5 (28.1) |

86.8 (30.4) |

91.5 (33.1) |

101.7 (38.7) |

100.8 (38.2) |

97.6 (36.4) |

93.3 (34.1) |

89.6 (32.0) |

78.5 (25.8) |

75.9 (24.4) |

101.7 (38.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.9 (1.6) |

38.1 (3.4) |

47.1 (8.4) |

59.5 (15.3) |

70.2 (21.2) |

79.6 (26.4) |

83.4 (28.6) |

81.5 (27.5) |

74.8 (23.8) |

63.2 (17.3) |

51.5 (10.8) |

38.9 (3.8) |

60.3 (15.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.7 (−6.3) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

39.6 (4.2) |

49.1 (9.5) |

59.2 (15.1) |

63.4 (17.4) |

62.0 (16.7) |

55.2 (12.9) |

44.7 (7.1) |

35.9 (2.2) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −23.3 (−30.7) |

−12.2 (−24.6) |

−5.7 (−20.9) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

37.4 (3.0) |

44.6 (7.0) |

41.3 (5.2) |

35.7 (2.1) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

−14.9 (−26.1) |

−23.3 (−30.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.43 (62) |

2.08 (53) |

2.77 (70) |

3.35 (85) |

3.92 (100) |

3.84 (98) |

3.94 (100) |

3.56 (90) |

3.51 (89) |

2.88 (73) |

3.27 (83) |

2.87 (73) |

38.42 (976) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 20.9 (−6.2) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

48.0 (8.9) |

58.0 (14.4) |

62.3 (16.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

55.3 (12.9) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.5 (1.4) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

41.6 (5.3) |

| Source: PRISM[48] | |||||||||||||

Attractions

[edit]

Cuyahoga Valley features natural, man-made, and private attractions, which is unusual for an American national park. The park includes compatible-use sites not owned by the federal government, such as four reservations of the Cleveland Metroparks, as well as four parks and one multipurpose trail of Summit Metro Parks.

The natural areas include forests, rolling hills, narrow ravines, wetlands, rivers, and waterfalls. About 100 waterfalls are located in the Cuyahoga Valley, with the most popular being the 65-foot (20 m) tall Brandywine Falls—the tallest waterfall in the park and the tallest in Northeast Ohio. The Ledges are a rock outcropping that provides a westward view across the valley's wooded areas. Talus caves are located among the boulders in the forest around the Ledges.

The park has many trails, most notably the 20-mile (32 km) Towpath Trail, which follows a former stretch of the 308-mile (496 km) Ohio and Erie Canal and is popular for hiking, bicycling, and running. Skiing and sled-riding are available during the winter at Kendall Hills.[49] Visitors can play golf, or take scenic excursions and railroad tours on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad during special events.[50]

The park also features preserved and restored displays of 19th and early 20th century sustainable farming and rural living, most notably the Hale Farm and Village, while catering to contemporary cultural interests with art exhibits, outdoor concerts, and theater performances in venues such as Blossom Music Center and Kent State University's Porthouse Theatre. In the mid-1980s, the park hosted the National Folk Festival.[51]

Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail

[edit]

The multi-purpose Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail was developed by the National Park Service and is the major trail through Cuyahoga Valley National Park. The trail traverses almost 21 mi (34 km) from Rockside Road in Independence in the north to Summit County's Bike & Hike trail in the south, following the Cuyahoga River for much of its length. Restrooms are available at several trailheads, and food and drink establishments are along Rockside Road, as well as the Boston Store in Peninsula, and at the seasonal farmer's market on Botzum Road. Three visitor centers are located along the path: the Canal Exploration Center, Boston Store, and the Hunt House. The trail connects to a Cleveland Metroparks trail at Rockside Road, which continues another 6 mi (9.7 km) north. The Summit County trail continues through Akron and further south through Stark and Tuscarawas counties to Zoar, Ohio, almost 70 mi (110 km) continuously, with a single 1 mi (1.6 km) interruption. Sections of the towpath trail outside of Cuyahoga Valley National Park are owned and maintained by various state and local agencies. The trail also meets the Buckeye Trail in the national park near Boston Store. Another section of the Summit County Bike & Hike Trail system is nearby, connecting to Brandywine Falls, Cleveland Metroparks' Bedford Reservation and the cities of Solon in Cuyahoga County, Hudson and Stow in Summit County, and Kent and Ravenna in Portage County.

Seasonally, the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) allows visitors to travel along the towpath from Rockside Road to Akron, embarking or disembarking at any of the stops along the way. The train is especially popular with bicyclists, and for viewing and photographing fall colors. CVSR is independently owned and operated.

History

[edit]

The Towpath Trail follows the historic route of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Before the canal was built, Ohio was a sparsely settled wilderness where travel was difficult and getting crops to market was nearly impossible. The canal, built between 1825 and 1832, provided a new transportation route from Cleveland on Lake Erie, to Portsmouth on the Ohio River. The canal connected Ohio to the rest of the eastern United States.[52] Numerous wayside exhibits provide information about canal features and sites of historic interest.[53]

Visitors can walk or ride along the same path that the mules used to tow the canal boats loaded with goods and passengers. The scene is different than it was then; the canal was full of water carrying a steady flow of boats. Evidence of beavers can be seen in many places along the trail.[52]

Stanford House (formerly Stanford Hostel)

[edit]Located in the scenic Cuyahoga Valley near Peninsula, Stanford House is a historic 19th-century farm home built in the 1830s by George Stanford, one of the first settlers in the Western Reserve. In 1978, the NPS purchased the property to serve as a youth hostel in conjunction with the American Youth Hostels (AYH) organization. In March 2011, Stanford Hostel became Stanford House, Cuyahoga Valley National Park's first in-park lodging facility. The home was renovated by the Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park and the National Park Service.[54]

Towpath trailheads

[edit]

Within the national park, trailhead parking for the towpath trail is available along Canal Road, from north to south, at:

- Lock 39—west of intersection with Rockside Road; 41°23′35″N 81°37′43″W / 41.39309°N 81.628565°W

- Canal Exploration Center—at Hillside Road; 41°22′21″N 81°36′47″W / 41.372624°N 81.613035°W

- Frazee House—south of Alexander Road, north of Sagamore Road; 41°21′09″N 81°35′33″W / 41.352443°N 81.592377°W

and along Riverview Road, from north to south, at:

- Station Road Bridge—east along with Chippewa Creek Drive; 41°19′07″N 81°35′17″W / 41.318618°N 81.587957°W

- Red Lock—east of the river, along Vaughn/Highland Road; 41°17′21″N 81°33′48″W / 41.289148°N 81.563379°W

- Boston Store—east on Boston Mills Road; 41°15′48″N 81°33′34″W / 41.263205°N 81.559408°W

- Peninsula Depot—east across river on Route 303, then N Locust Street, and W Mill Street to parking lot; 41°14′36″N 81°32′57″W / 41.243331°N 81.549186°W

- Lock 28—also called Deep Lock; south of Major Road; 41°13′48″N 81°33′17″W / 41.229917°N 81.554756°W

- Hunt House—at Bolanz Road; 41°12′01″N 81°34′19″W / 41.200288°N 81.57201°W

- Ira Road—just north of intersection; 41°11′04″N 81°34′59″W / 41.184467°N 81.583038°W

- Botzum station—south of Bath Road; 41°09′30″N 81°34′26″W / 41.158453°N 81.573788°W.[55]

Geology

[edit]

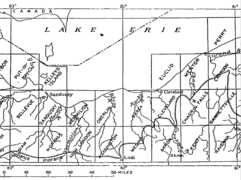

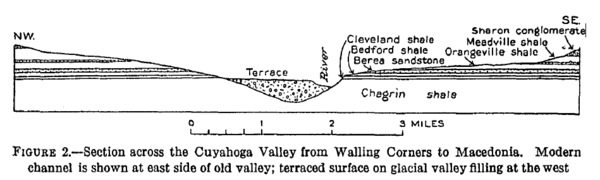

The "V" course of the Cuyahoga River is rather unusual, first flowing southwest, and then abruptly turning north to drain into Lake Erie not far from its origin. The left arm of this "V", flowing north through the park, corresponds to an older preglacial valley, while the right arm corresponds to relatively new drainage. The new segment cut into the old at Cuyahoga Falls, the base of the "V". Other streams have made routes into the Cuyahoga preglacial valley by cutting gorges with waterfalls such as those found along the Tinkers, Brandywine and Chippewa Creeks. These waterfalls form as flowing water erodes the Bedford Shale, which underlies the more resistant Berea Sandstone. Glacial drift fills the valley to a depth of 400 feet (120 m). This fill is very complex due to ponding in front of the ice before and after each glaciation. Beach deposits, gravel bars and other shoreline deposits from Lake Maumee are found in the valley, as are gravels from the time of Lake Arkona, and ridges marking the shores of Lake Whittlesey, Lake Warren, and Lake Wayne.[56][57]

A noticeable remnant of the Wisconsin glaciation is the Defiance moraine, which trends from Defiance in western Ohio, across the state into Pennsylvania. As Cushing et al. point out, "The Defiance moraine represents the last notable stand of the glacial front in this region." The moraine varies in width from 2–4 mi (3.2–6.4 km), and according to Leverett, "it is like a broad wave whose crest stands 20 to 50 feet above the border of the plain outside it." This moraine forms a lobe that protrudes south into the valley for 8 mi (13 km) all the way to Peninsula, the lobe being 6 mi (9.7 km) wide at the north end, tapering to 3 mi (4.8 km) wide at the south end. Kames and eskers mark the terrain south of this moraine up to the southern extent of the glaciation.[56]: 581–584 [57]: 63–64, 96 [58]

The Berea Sandstone and the Bedford Shale were deposited in a river delta environment in the Lower Mississippian. River channels were incised into the Bedford Shale and subsequently these channels were filled by the Berea Sandstone. Besides setting the stage for majestic gorges and waterfalls within the valley, they have provided an economic use as well. The Berea Sandstone was quarried in Berea for grindstones and building stones, while the lowermost part of the Bedford Shale was quarried in South Euclid and Cleveland Heights for its bluestone.[57]: 109–111 [59]

The Sharon Conglomerate is a Lower Pennsylvanian formation composed of sandstone and conglomerate which forms, according to Cushing et al., "disconnected patches or outliers that cap the highest hills... these outliers stand boldly above the surrounding country" due to its resistance to erosion. The Boston Ledges are the most noteworthy example. As the Mississippian shale underneath is washed away, huge blocks of the Sharon result from the settling. As Cushing et al. explain, "frost action aids in pushing these blocks apart, cracks are widened into caves, and a tangle of blocks results, separated by passages of uneven widths."[57]: 54–57

Shale gas has been produced in the area since 1883, when H.A. Mastick's well was drilled in the Rockport Township to a depth of 527 ft (161 m), yielding 21,643 cubic feet (612.9 m3) of gas daily. A gas boom occurred in 1914–1915, and by 1931, several hundred gas wells were producing from the Devonian Huron shale. Production came from shales 1,250 ft (380 m) thick at depths from 400–1,840 ft (120–560 m). Pressures were 3–135 psi (21–931 kPa) flowing less than 20,000 cubic feet (570 m3) of gas daily, but was sufficient to furnish light for a house or two, and sometimes heat. As Cushing et al. pointed out in the 1930s, "there are vast amounts of petroleum in the Devonian shales." Since then, the Marcellus Shale and the deeper Utica Shale have shown their economic potential.[57]: 115–116, 123

-

Map tracing the extent of the Defiance Moraine

-

Geologic map of surface glacial features

-

Ohio glacial boundary

-

Geologic map of rock outcrops

-

Geologic cross section

Visitor centers

[edit]The Canal Exploration Center is located along Canal Road at Hillside Road in Valley View, south of Rockside Road. The visitor center contains interactive maps and games related to the history of the canal, especially the years from 1825 to 1876. The canal-era building once served canal boat passengers waiting to pass through the Ohio and Erie Canal's Lock 38.[60]

Boston Store was constructed in 1836 and is located just east of Riverview Road. The building was used as a warehouse, store, post office, and a general gathering place. The visitor center has a museum featuring exhibits on canal boat-building. A short video is available, as well as maps, brochures and NPS passport stamps.[28]

The Hunt House at Riverview and Bolanz Roads is typical of late-19th-century family farms in the Cuyahoga Valley. Visitors can obtain information about park activities and see exhibits about the area's agricultural history. The farm is an ideal starting point for a hike or a bicycle ride as it is adjacent to the canal towpath trail.[28]

The Frazee House on Canal Road in Valley View south of Rockside Road was constructed from 1825 to 1826, during the same years the northern section of the canal was dug. The house is a fine example of a Western Reserve home and features exhibits relating to architectural styles, construction techniques, and the Frazee family.[61]

Points of historic interest

[edit]| Site | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Canal Exploration Center |  |

Exhibits related to the Ohio and Erie Canal history are available at the Canal Exploration Center. The exhibits are housed in a renovated canal-era tavern that had such a colorful reputation that it was called "Hell's Half Acre". Lock 38 is located in the front.[60] |

| Ohio and Erie Canal related structures |  |

The Ohio and Erie Canal was constructed between 1825 and 1832, providing Ohio with a transportation system that permitted residents to conduct trade with the world. While it stopped functioning after the Great Flood of 1913, remnants and ruins of canal-related structures can be seen alongside the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail. Wayside exhibits explain the function of many of the structures visible from the trail.[62][53] |

| Frazee House |

|

The Frazee House was under construction in 1825 when the canal was dug through its front yard. The house was built in the Western Reserve architectural style.[61] |

| Boston Store (Boston Mill Visitor Center) |

|

This early canal-era building was owned by the Boston Land and Manufacturing Company. The store has numerous canal boat-building exhibits.[28] |

| Peninsula Depot |

|

The Peninsula Depot of the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) is located on West Mill Street in the village of Peninsula. The depot was originally in the village of Boston, but was moved to Peninsula in the late 1960s. The building may be the only surviving combination station from the Valley Railway, which operated between Cleveland and Tuscarawas County in the late 19th century. The depot is an operating station for CVSR train rides.[28] |

| Everett Covered Bridge |

|

The Everett Covered Bridge—the only covered bridge in Summit County—was constructed after a local resident was killed attempting to cross the swollen Furnace Run in 1877. The bridge was destroyed by storm floodwaters in 1975 and reconstructed by the National Park Service in 1986. The bridge is located on Everett Road about 1⁄2 mile (800 m) west of Riverview Road near Everett Village.[63] |

| Brandywine Village |

|

Brandywine Village was conceived and founded by George Wallace, who built a sawmill next to Brandywine Falls in 1814. He encouraged others to move to the area, including his brother-in-law, who built a grist mill on the opposite side of the falls. With inexpensive land available and the presence of mills to provide lumber, flour, and corn meal, Brandywine Village began to grow. A couple of buildings remain from the village, and historic photos and remnants of building foundations can also be seen.[64] |

| Civilian Conservation Corps structures |

|

The Civilian Conservation Corps was responsible for the construction of several structures in the valley. Happy Days Lodge and the shelters at the Ledges, Octagon, and Kendall Lake were built of American chestnut in the late 1930s. All four structures are in the Virginia Kendall Unit of the park.[65][66] |

| Stanford House |

|

James Stanford moved to Boston Township immediately after surveying and naming it in 1806. He and his wife Polly and son George were the first homesteaders in what is today Cuyahoga Valley National Park. His son George built the stately Greek revival home in about 1830. The house accommodates meetings and retreats as a day-use facility, and tourists as a moderately priced overnight facility with nine bedrooms. The house had previously served as a youth hostel.[67][68][69] |

| Hale Farm and Village |

|

Hale Farm and Village is an outdoor living history museum. Costumed interpreters describe life in the Western Reserve. The village features 21 historic buildings and many talented craftspeople. The site is operated by the Western Reserve Historical Society. Craft demonstrations include glassblowing, candlemaking, broommaking, spinning and weaving, cheesemaking, blacksmithing, woodworking, sawmilling, hearth cooking, and pottery making. The farm also has oxen, sheep, cows, and gardens.[70] |

National Register of Historic Places

[edit]All properties listed here are open to the public, though some in a limited way—see Status column. Many of the NRHP sites found in the full list are in private ownership and are not listed here.[72]

| District or site |

County | Locale |

Status |

Address |

Register date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valley Railway Historic District | Both | Independence to Akron | Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad scenic train rides | Cuyahoga Valley between Rockside Road and Howard Street at Little Cuyahoga Valley | 1985/05/17 |

| Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Bridge | Cuyahoga | Bedford | Tinkers Creek | 1975/07/24 | |

| Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge (state highway bridge) | Cuyahoga | Brecksville—41°19′17″N 081°35′14″W / 41.32139°N 81.58722°W[73] | Ohio State Route 82 and Cuyahoga River (also in Northfield, Summit County, Ohio); best viewed from Station Road Bridge Trailhead on the Towpath Trail (Riverview Road just south of Ohio State Route 82) | 1986/01/06 | |

| Brecksville Trailside Museum (Cleveland Metroparks Nature Center) | Cuyahoga | Brecksville | Chippewa Creek Drive off Ohio State Route 82 | 1992 | |

| Stephen Frazee House | Cuyahoga | Valley View | CVNP visitor center with limited open hours | 7733 Canal Road | 1976/05/04 |

| Lock 37 and Spillway | Cuyahoga | Valley View | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Fitzwater Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 38 and Spillway | Cuyahoga | Valley View | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Hillside Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 39 and Spillway | Cuyahoga | Valley View | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Canal Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Inn at Lock 38 | Cuyahoga | Valley View—41°22′21″N 81°36′47″W / 41.372624°N 81.613035°W | CVNP Canal Exploration Center | 7104 Canal Road, Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | 1979/12/11 |

| Tinkers Creek Aqueduct | Cuyahoga | Valley View—41°21′53″N 081°36′32″W / 41.36472°N 81.60889°W[74] | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Tinkers Creek | 1979/12/11 |

| Wilson Feed Mill | Cuyahoga | Valley View | feed and grain store | 7604 Canal Road, Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | 1979/12/17 |

| Ohio and Erie Canal | Cuyahoga | Valley View | National Historic Landmark, 1966/11/13 | Ohio State Route 631 | 1965/11/13 |

| Hale, Jonathan Homestead - Hale Farm and Village | Summit | Bath | 2686 Oak Hill Road | 1973/04/23 | |

| Boston Land and Manufacturing Company Store (a.k.a. Boston Store) | Summit | Boston | CVNP visitor center with limited open hours | Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, Boston Mills Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 32 | Summit | Boston | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | 800 ft (240 m) north of Boston Mills Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Boston Mills Historic District | Summit | Boston | most buildings are private | Boston Mills Road, Stanford Road & Main Street | 1992/11/09 |

| Lock 33 | Summit | Boston vicinity | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | 1 mi (1.6 km) south of Highland Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Hunt House | Summit | Cuyahoga Falls | limited open hours | 2049 Bolanz Road | 1993/03/12 |

| Station Road Bridge | Summit | Brecksville vicinity—41°19′07″N 81°35′17″W / 41.318618°N 81.58795741°W[75] | East of Brecksville at Cuyahoga River | 1979/03/07 | |

| Lock 27 | Summit | Everett | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Approx. 400 ft (120 m) east of intersection of Riverview and Everett Roads | 1993/03/12 |

| Furnace Run Aqueduct | Summit | Everett vicinity | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Furnace Run | 1979/12/11 |

| Everett Historic District | Summit | Everett | village is open to the public; some buildings are private residences; NPS buildings have no visitor facilities | Everett and Riverview Roads | 1994/01/14 |

| Everett Knoll Complex | Summit | Everett | Hopewell site dating to ~200 AD | South of Everett Road | 1977/05/11 |

| Lock 26 | Summit | Ira | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | 3.3 mi (5.3 km) north of Ira Road | 1979/12/11 |

| Wallace Farm | Summit | Northfield vicinity | open to patrons of the bed & breakfast only (Inn at Brandywine Falls) | 8230 Brandywine Road | 1985/06/27 |

| Everett Covered Bridge | Summit | Peninsula | destroyed by floodwaters in 1975; reconstructed in 1986 | SW of Peninsula on Everett Road over Furnace Creek | 1973/05/23 |

| Lock 28 | Summit | Peninsula | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Deep Lock Quarry Metro Park | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 29 and Aqueduct | Summit | Peninsula | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | off Ohio State Route 303 | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 30 and Feeder Dam | Summit | Peninsula | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | off Ohio State Route 303 | 1979/12/11 |

| Lock 31 | Summit | Peninsula | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | 200 ft (61 m) east of Cuyahoga River and approx. 0.5 mi (800 m) south of Ohio Turnpike | 1979/12/11 |

| Peninsula Village Historic District | Summit | Peninsula—41°14′32″N 81°32′57″W / 41.24222°N 81.54917°W | most buildings are private; some are retail stores | Both sides of Ohio State Route 303 | 1974/08/23 |

| George Stanford Farm | Summit | Peninsula vicinity | hosts meetings and retreats as a day-use facility; overnight accommodations | 6093 Stanford Road | 1982/02/17 |

| Stumpy Basin | Summit | Peninsula vicinity | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | 200 ft (61 m) east of Cuyahoga River and approx, 0.5 mi (800 m) south of Ohio Turnpike | 1979/12/11 |

| Virginia Kendall Historic District | Summit | Peninsula vicinity | shelter, restrooms, winter sports center | Truxell Road | 1997/01/10 |

| Lock 34 | Summit | Sagamore Hills | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Highland Road | 1979/12/17 |

| Lock 35 | Summit | Sagamore Hills | Formerly part of Ohio and Erie Canal, currently on the Towpath Trail | Off Ohio State Route 82 | 1979/12/11 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "National Reports". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

Click on Park Acreage Reports (1997 – Last Calendar/Fiscal Year), then select By Park, Calendar Year, <choose year>, and then click the View PDF Report button – the area used here is Gross Area Acres which appears in the final column of the report

- ^ Chen, Eve (2024-03-31). "National parks by the numbers: America's oldest, largest, most visited". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ Chen, Eve. "What is the most visited national park in the US? Answers to your biggest park questions". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ Brose, David (January 1974). "The Everett Knoll: A Late Hopewellian Site in Northeastern Ohio". Ohio Journal of Science. 74 (1).

- ^ "List of Federal and State Recognized Tribes". ncsl.org. National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ a b c Stockwell, Mary (2016). The other Trail of Tears : the removal of the Ohio Indians (First Westholme Paperback ed.). Yardley, Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-1594162589. OCLC 940521412.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hìtakonanulaxk (1994). The grandfathers speak : native American folk tales of the Lenapé people. New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 978-1566561297. OCLC 29218801.

- ^ "Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850". Contested Territories: Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850. Michigan State University Press. 2012. ISBN 9781611860450. JSTOR 10.14321/j.ctt7zt59g.10. [verification needed]

- ^ a b Soderlund, Jean R. (2015). "Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn". Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812246476. JSTOR j.ctt13x1nzp.

- ^ a b "Who are the Lenape?". lenape-nation.org. Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "About Us". nanticoke-lenapetribalnation.org. Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation. Archived from the original on 2020-02-23. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware - Welcome!". lenapeindiantribeofdelaware.com. Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ "Fulfilling a Prophecy". www.penn.museum. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ a b Kraft, Herbert C. (1986). The Lenape : archaeology, history, and ethnography. Newark: New Jersey Historical Society. ISBN 978-0911020144. OCLC 13062917.

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G. (1885). The Lenâpé And Their Legends: With the Complete Text And Symbols of the Walam Olum, a New Translation, And an Inquiry Into Its Authenticity. Philadelphia: D.G. Brinton.

- ^ Schutt, Amy C. (2007). Peoples of the river valleys : the odyssey of the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812203790. OCLC 859160719.

- ^ Richter, Daniel K. (1999). "'Believing That Many of the Red People Suffer Much for the Want of Food': Hunting, Agriculture, and a Quaker Construction of Indianness in the Early Republic". Journal of the Early Republic. 19 (4): 601–628. doi:10.2307/3125135. JSTOR 3125135.

- ^ "Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850". Contested Territories: Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850. Michigan State University Press. 2012. ISBN 9781611860450. JSTOR 10.14321/j.ctt7zt59g.9.

- ^ "Portage Path - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Bragdon, Kathleen J. (2001). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Northeast. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/brag11452. ISBN 9780231504355. JSTOR 10.7312/brag11452.

- ^ "Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850". Contested Territories: Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850. Michigan State University Press. 2012. ISBN 9781611860450. JSTOR 10.14321/j.ctt7zt59g.10.

- ^ "Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850". Contested Territories: Native Americans and Non-Natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850. Michigan State University Press. 2012. ISBN 9781611860450. JSTOR 10.14321/j.ctt7zt59g.9.

- ^ "Delaware Nation - About Us". Delaware Nation. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Hale, Duane K. (1987). Peacemakers on the frontier: A history of the Delaware Tribe of western Oklahoma. Anadarko, Oklahoma: Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press.

- ^ Farley, Alan W. (1995). The Delaware Indians in Kansas: 1829-1867. Kansas City, Kansas: Kansas Historical Society.

- ^ "The Ledges" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. June 1, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley: Ohio's National Park" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Visitor Centers" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 29, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Operating Hours & Seasons" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. October 29, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "The Cuyahoga River". nps.gov. National Park Service. January 4, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ Adler, Jonathan H. (June 22, 2014). "The fable of the burning river, 45 years later". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Cuyahoga Valley National Park – Park Statistics". nps.gov. National Park Service. August 7, 2017. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "1974/12/27 HR7077 Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area Ohio" (PDF). fordlibrarymuseum.gov. Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Almond, Peter (2022). A Love Letter to Cleveland: The Memoirs of a Brit Journalist with the Cleveland Press 1970-82. MSL Academic Endeavors, Imprint of the Cleveland State University Michael Schwartz Library. ISBN 978-1-936323-98-2.

- ^ Cockrell, Ron (1992). A Green Shrouded Miracle: The Administrative History of Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, Ohio (PDF). National Park Service.

- ^ a b "Krejci Dump- A story of Transformation" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 10, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2018. "Image caption: Krejic dump site in 2013 after clean up and restoration."

- ^ Downing, Bob (December 2, 2001). "Dump cleanup costliest for parks". Akron Beacon Journal. Akron. Retrieved February 8, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "3M to pay $15.5 million for Krejci Dump". justice.gov. United States Department of Justice. February 7, 2002. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ "Krejci: Recent Updates". National Park Service. May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-10-25. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

August 29, 2012...remediation goals for the 46-acre former dump site have been met; February 3, 2015:..restoring the ecology to its native condition

- ^ Rep. Ralph Regula [R-OH16, 1973-2009] (n.d.). "H.R. 4578 (106th): Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2001: Overview". govtrack.us. GovTrack, Civic Impulse, LLC. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Downing, Bob (March 30, 2024). "From 'national recreation area' to 'national park': The story behind CVNP's evolution". Akron Beacon Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ McCarty, James F. (June 5, 2012). "Coliseum Grasslands Offer Intimate Views of Some of the Most-threatened Bird Species: Aerial View". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Former Coliseum Property". nps.gov. National Park Service. August 28, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park signs Sister Park agreement with England's Dartmoor National Park". Ideastream Public Media. 2024-06-07. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ "Mammals - Cuyahoga Valley National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". ars.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2019-07-04. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "Time Series Values for Individual Locations". prism.oregonstate.edu. PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "Winter Sports". National Park Service. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad". cvsr.com. Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "National Folk Festival, Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, 1983". Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. August 31, 2018. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Interactive Tow-Path Tour". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Life & Times of the Stanford House". conservancyforcvnp.org. Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park. December 15, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. March 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Leverett, Frank (1902). Glacial Formations and Drainage Features of the Erie and Ohio Basins, USGS Monograph Vol. XLI. Washington: US Government Printing Office. p. 216.

- ^ a b c d e Cushing, H.P.; Leverett, Frank; Van Horn, Frank (1931). Geology and Mineral Resources of the Cleveland District, Ohio, USGS Bulletin 818. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 9, 16–19, 68–79. doi:10.3133/b818.

- ^ Swinford, Edward; Pavey, Richard; Larsen, Glenn (2006). Soller (ed.). New Map of the Surficial Geology of the Lorain and Put-in-Bay 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangles, Ohio, in Digital Mapping Techniques '06- Workshop Proceedings. Columbus: USGS Open-File Report 2007-1285 2007. p. 178.

- ^ Pepper, James; De Witt, Wallace; Demarest, David (1954). Geology of the Bedford Shale and Berea Sandstone in the Appalachian Basin, USGS Professional Paper 259. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 12, 70–71.

- ^ a b "Canal Exploration Center" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. April 24, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Western Reserve Pioneers" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. April 10, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Ohio and Erie Canal". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Everett Road Covered Bridge". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Brandywine Village". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Ledges Area Trails" (PDF). National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2018.

- ^ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Kendall Lake Area Trails" (PDF). National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2018.

- ^ "The George Stanford House". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

- ^ "Lodging - Stanford House". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018.

- ^ "Stanford House". Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018.

- ^ "Hale Farm and Village". Western Reserve Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 10, 2003.

- ^ "Points of Historic Interest". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places - Cuyahoga Valley National Park". npgallery.nps.gov. National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ "Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ "Tinkers Creek Aqueduct". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ "Station Road Bridge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

Bibliography

[edit]- "A Green Shrouded Miracle: The Administrative History of Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, Ohio". National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2007-05-06.

- "Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

- "The Ohio & Erie Canal: Catalyst of Economic Development for Ohio, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan". National Park Service, Department of the Interior. 2001-08-24.

- "Cuyahoga Valley National Park – Official Site". National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

- "The National Parks: Index 2012–2016" (PDF). National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Cuyahoga Valley Trails Council (2007). The Trail Guide to Cuyahoga Valley National Park, 3rd Edition, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-040-9

External links

[edit]- Official website

of the National Park Service

of the National Park Service - Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park

- Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad

- Hit the Rails for the Best Cuyahoga Valley Experience – a National Geographic Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad article

- IUCN Category II

- Cuyahoga Valley National Park

- Protected areas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio

- Protected areas of Summit County, Ohio

- Protected areas established in 1974

- Civilian Conservation Corps in Ohio

- Ohio and Erie Canalway National Heritage Area

- 2000 establishments in Ohio

- 1974 establishments in Ohio

- National parks in Ohio