Protectorate

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law.[1] It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its internal affairs, while still recognizing the suzerainty of a more powerful sovereign state without being a possession.[2][3][4] In exchange, the protectorate usually accepts specified obligations depending on the terms of their arrangement.[4] Usually protectorates are established de jure by a treaty.[2][3] Under certain conditions—as with Egypt under British rule (1882–1914)—a state can also be labelled as a de facto protectorate or a veiled protectorate.[5][6][7]

A protectorate is different from a colony as it has local rulers, is not directly possessed, and rarely experiences colonization by the suzerain state.[8][9] A state that is under the protection of another state while retaining its "international personality" is called a "protected state", not a protectorate.[10][a]

History

[edit]Protectorates are one of the oldest features of international relations, dating back to the Roman Empire. Civitates foederatae were cities that were subordinate to Rome for their foreign relations. In the Middle Ages, Andorra was a protectorate of France and Spain. Modern protectorate concepts were devised in the nineteenth century.[11]

Typology

[edit]Foreign relations

[edit]In practice, a protectorate often has direct foreign relations only with the protector state, and transfers the management of all its more important international affairs to the latter.[12][4][2][3] Similarly, the protectorate rarely takes military action on its own but relies on the protector for its defence. This is distinct from annexation, in that the protector has no formal power to control the internal affairs of the protectorate.

Protectorates differ from League of Nations mandates and their successors, United Nations trust territories, whose administration is supervised, in varying degrees, by the international community. A protectorate formally enters into the protection through a bilateral agreement with the protector, while international mandates are stewarded by the world community-representing body, with or without a de facto administering power.

Protected state

[edit]A protected state has a form of protection where it continues to retain an "international personality" and enjoys an agreed amount of independence in conducting its foreign policy.[10][13]

For political and pragmatic reasons, the protection relationship is not usually advertised, but described with euphemisms such as "an independent state with special treaty relations" with the protecting state.[14] A protected state appears on world maps just as any other independent state.[a]

International administration of a state can also be regarded as an internationalized form of protection, where the protector is an international organisation rather than a state.[15]

Colonial protection

[edit]Multiple regions—such as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, the Colony and Protectorate of Lagos, and similar—were subjects of colonial protection.[16][17] Conditions of protection are generally much less generous for areas of colonial protection. The protectorate was often reduced to a de facto condition similar to a colony, but with the pre-existing native state continuing as the agent of indirect rule. Occasionally, a protectorate was established by another form of indirect rule: a chartered company, which becomes a de facto state in its European home state (but geographically overseas), allowed to be an independent country with its own foreign policy and generally its own armed forces.[citation needed]

In fact, protectorates were often declared despite no agreement being duly entered into by the state supposedly being protected, or only agreed to by a party of dubious authority in those states. Colonial protectors frequently decided to reshuffle several protectorates into a new, artificial unit without consulting the protectorates, without being mindful of the theoretical duty of a protector to help maintain a protectorate's status and integrity. The Berlin agreement of February 26, 1885, allowed European colonial powers to establish protectorates in Black Africa (the last region to be divided among them) by diplomatic notification, even without actual possession on the ground. This aspect of history is referred to as the Scramble for Africa. A similar case is the formal use of such terms as colony and protectorate for an amalgamation—convenient only for the colonizer or protector—of adjacent territories, over which it held (de facto) sway by protective or "raw" colonial power.[citation needed]

Amical protection

[edit]In amical protection—as of United States of the Ionian Islands by Britain—the terms are often very favourable for the protectorate.[18][19] The political interest of the protector is frequently moral (a matter of accepted moral obligation, prestige, ideology, internal popularity, or dynastic, historical, or ethnocultural ties). Also, the protector's interest is in countering a rival or enemy power—such as preventing the rival from obtaining or maintaining control of areas of strategic importance. This may involve a very weak protectorate surrendering control of its external relations but may not constitute any real sacrifice, as the protectorate may not have been able to have a similar use of them without the protector's strength.

Amical protection was frequently extended by the great powers to other Christian (generally European) states, and to states of no significant importance.[ambiguous] After 1815, non-Christian states (such as the Chinese Qing dynasty) also provided amical protection of other, much weaker states.

In modern times, a form of amical protection can be seen as an important or defining feature of microstates. According to the definition proposed by Dumienski (2014): "microstates are modern protected states, i.e. sovereign states that have been able to unilaterally depute certain attributes of sovereignty to larger powers in exchange for benign protection of their political and economic viability against their geographic or demographic constraints".[20]

Argentina's protectorates

[edit] Liga Federal (1815–1820)

Liga Federal (1815–1820) Chile (1817–1818)

Chile (1817–1818) Republic of Tucumán (1820–1821)

Republic of Tucumán (1820–1821) Peru (1820–1822)

Peru (1820–1822) Gobierno del Cerrito (1843–1851)

Gobierno del Cerrito (1843–1851) Paraguay (1876)

Paraguay (1876)

Brazil's protectorates

[edit] Republic of Acre (1899–1903)

Republic of Acre (1899–1903)- Paraguay (1869–1876)

- Uruguay (1828–1835)

Belgium protectorates

[edit]Belgium controlled several territories and concessions during the colonial era, principally the Belgian Congo (modern DR Congo) from 1908 to 1960, Ruanda-Urundi (modern Rwanda and Burundi) from 1922 to 1962, and Lado Enclave (modern Central Equatoria province in South Sudan) from 1884 to 1910. It also had small concessions in Guatemala (1843–1854) and Belgian concession of Tianjin in China (1902–1931) and was a co-administrator of the Tangier International Zone in Morocco.

Roughly 98% of Belgium's overseas territory was just one colony (about 76 times larger than Belgium itself) – known as the Belgian Congo. The colony was founded in 1908 following the transfer of sovereignty from the Congo Free State, which was the personal property of Belgium's king, Leopold II. The violence used by Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction had led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country. Belgian rule in the Congo was based on the "colonial trinity" (trinité coloniale) of state, missionary and private company interests. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Congo experienced extensive urbanization and the administration aimed to make it into a "model colony". As the result of a widespread and increasingly radical pro-independence movement, the Congo achieved independence, as the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville in 1960.

Of Belgium's other colonies, the most significant was Ruanda-Urundi, a portion of German East Africa, which was given to Belgium as a League of Nations Mandate, when Germany lost all of its colonies at the end of World War I. Following the Rwandan Revolution, the mandate became the independent states of Burundi and Rwanda in 1962.

British Empire's protectorates and protected states

[edit]Americas

[edit]Europe

[edit]

Malta Protectorate (1800–1813; de jure part of the Kingdom of Sicily but under British protection)

Malta Protectorate (1800–1813; de jure part of the Kingdom of Sicily but under British protection)

(Crown Colony of Malta proclaimed in 1813)

(Crown Colony of Malta proclaimed in 1813)

Ionian islands (1815–1864; a Greek state and amical protectorate of Great Britain between 1815 and 1864)

Ionian islands (1815–1864; a Greek state and amical protectorate of Great Britain between 1815 and 1864) British Cyprus (1878–1914; put under British military administration (1914–22) then proclaimed a Crown Colony (1922–60))

British Cyprus (1878–1914; put under British military administration (1914–22) then proclaimed a Crown Colony (1922–60))

South Asia

[edit] Cis-Sutlej states[21][22] (1809–1862)

Cis-Sutlej states[21][22] (1809–1862) Kingdom of Nepal (1816–1923; protected state)[14]

Kingdom of Nepal (1816–1923; protected state)[14] Kingdom of Sikkim (1861–1947), (1947–1972)[23]

Kingdom of Sikkim (1861–1947), (1947–1972)[23] Maldive Islands (1776–1965, 1965–1968, 1968–1990)[24]

Maldive Islands (1776–1965, 1965–1968, 1968–1990)[24]- Various British Raj princely states (1845–1947)

Bhutan (1906–1947 and 1948; protected state)[14]

Bhutan (1906–1947 and 1948; protected state)[14]

West and Central Asia

[edit] British Residency of the Persian Gulf (1822–1971; headquarters based in Bushire, Persia)

British Residency of the Persian Gulf (1822–1971; headquarters based in Bushire, Persia)

Bahrain (1880–1971; protected state)[14]

Bahrain (1880–1971; protected state)[14] Sheikhdom of Kuwait (1899–1961; protected state)[14]

Sheikhdom of Kuwait (1899–1961; protected state)[14] Qatar, protected state (1916–1971)

Qatar, protected state (1916–1971) Trucial States (1892–1971; precursor state of the modern UAE, protected states)[14]

Trucial States (1892–1971; precursor state of the modern UAE, protected states)[14]

Abu Dhabi (1820–1971)

Abu Dhabi (1820–1971) Ajman (1820–1971)

Ajman (1820–1971) Dubai (1835–1971)

Dubai (1835–1971) Fujairah (1952–1971)

Fujairah (1952–1971) Ras Al Khaimah (1820–1971)

Ras Al Khaimah (1820–1971) Sharjah (1820–1971)

Sharjah (1820–1971)

Kalba (1936–1951)

Kalba (1936–1951)

Umm al-Qaiwain (1820–1971)

Umm al-Qaiwain (1820–1971)

Muscat and Oman (1892–1971; informal, protected state)[25][26]

Muscat and Oman (1892–1971; informal, protected state)[25][26]

Aden Protectorate (1872–1963; precursor state of South Yemen)[27]

Aden Protectorate (1872–1963; precursor state of South Yemen)[27]

- Eastern Protectorate States (mostly in Hadhramaut) (1963–1967; later the Protectorate of South Arabia)

- Western Protectorate States (1959 and 1962–1967; later the Federation of South Arabia, including Aden Colony)

Wahidi Sultanates (these included: Balhaf, Azzan, Bir Ali, and Habban)

Wahidi Sultanates (these included: Balhaf, Azzan, Bir Ali, and Habban) Beihan

Beihan Dhala and Qutaibi

Dhala and Qutaibi Fadhli

Fadhli Lahej

Lahej Lower Yafa

Lower Yafa Audhali

Audhali Haushabi

Haushabi Upper Aulaqi Sheikhdom

Upper Aulaqi Sheikhdom Upper Aulaqi Sultanate

Upper Aulaqi Sultanate Lower Aulaqi

Lower Aulaqi Alawi

Alawi Aqrabi

Aqrabi Dathina

Dathina Shaib

Shaib

Emirate of Afghanistan (1879–1919; protected state)[14]

Emirate of Afghanistan (1879–1919; protected state)[14] Afghanistan (1919–1947, 1948, 1950, 1956)

Afghanistan (1919–1947, 1948, 1950, 1956)

Africa

[edit]

British Somaliland (1884–1960)[27]

British Somaliland (1884–1960)[27] Bechuanaland Protectorate (1885–1966)

Bechuanaland Protectorate (1885–1966) Barotseland Protectorate (1889–1980)

Barotseland Protectorate (1889–1980) Nyasaland Protectorate (1893–1964)

Nyasaland Protectorate (1893–1964)

British Central Africa Protectorate (1889–1907)

British Central Africa Protectorate (1889–1907)

Sultanate of Zanzibar (1890–1963)

Sultanate of Zanzibar (1890–1963)- Sultanate of Wituland (1890–1923)

Gambia Colony and Protectorate* (1894–1971)

Gambia Colony and Protectorate* (1894–1971) Uganda Protectorate (1894–1962)

Uganda Protectorate (1894–1962) East Africa Protectorate (1895–1920)

East Africa Protectorate (1895–1920) Sierra Leone Protectorate* (1896–1961)

Sierra Leone Protectorate* (1896–1961) Nigeria* (1914–1963)

Nigeria* (1914–1963) Northern Nigeria Protectorate (1900–1914)

Northern Nigeria Protectorate (1900–1914) Swaziland (1903–1968)

Swaziland (1903–1968) Southern Nigeria Protectorate (1900–1914)

Southern Nigeria Protectorate (1900–1914) Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (British protectorate) (1901–1957)/(1957-1960)

Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (British protectorate) (1901–1957)/(1957-1960) Sultanate of Egypt (1914–1922)

Sultanate of Egypt (1914–1922) Kenya Protectorate* (1920–1963'1964)

Kenya Protectorate* (1920–1963'1964) Kingdom of Egypt (1922–1936)

Kingdom of Egypt (1922–1936) Northern Rhodesia (1924–1964'1965'1980)

Northern Rhodesia (1924–1964'1965'1980)

*protectorates which existed alongside a colony of the same name

De facto

[edit] Khediviate of Egypt (1882–1913)

Khediviate of Egypt (1882–1913)

Oceania

[edit] Territory of Papua (1884–1888)

Territory of Papua (1884–1888) Tokelau (1877–1916)

Tokelau (1877–1916) Cook Islands (1888–1893)

Cook Islands (1888–1893) Gilbert and Ellice Islands (1892–1916)

Gilbert and Ellice Islands (1892–1916) British Solomon Islands (1893–1978)

British Solomon Islands (1893–1978) Niue (1900–1901)

Niue (1900–1901) Tonga (1900–1970)

Tonga (1900–1970)

Southeast Asia

[edit] British North Borneo (1888–1946)

British North Borneo (1888–1946) Brunei (1888–1984)

Brunei (1888–1984) Raj of Sarawak (1888–1946)

Raj of Sarawak (1888–1946) Federation of Malaya (1948–1957)

Federation of Malaya (1948–1957)

Federated Malay States (1895–1946)

Federated Malay States (1895–1946)

Negeri Sembilan (1888–1895)

Negeri Sembilan (1888–1895)

Sungai Ujong (1874–1888)

Sungai Ujong (1874–1888) Jelebu (1886–1895)

Jelebu (1886–1895)

Pahang (1888–1895)

Pahang (1888–1895) Perak (1874–1895)

Perak (1874–1895) Selangor (1874–1895)

Selangor (1874–1895)

Unfederated Malay States (1904/09–1946)

Unfederated Malay States (1904/09–1946)

China's protectorates

[edit]Dutch Empire's protectorates

[edit]Various sultanates in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia):[35][36][37]

- Tarumon Kingdom (1830–1946)

Langkat Sultanate (26 October 1869 – December 1945)

Langkat Sultanate (26 October 1869 – December 1945) Deli Sultanate (22 August 1862 – December 1945)

Deli Sultanate (22 August 1862 – December 1945) Asahan Sultanate (27 September 1865 – December 1945)

Asahan Sultanate (27 September 1865 – December 1945)- Bila (1864–1946)

Tasik (Kota Pinang) (1865 – December 1945)

Tasik (Kota Pinang) (1865 – December 1945) Siak Sultanate (1 February 1858 – 1946)

Siak Sultanate (1 February 1858 – 1946)- Sungai Taras (Kampong Raja) (1864–1916)

- Panei (1864–1946)

Sultanate of Serdang (1865 – December 1945)

Sultanate of Serdang (1865 – December 1945)- Indragiri Sultanate (1838 – September 1945)

Jambi Sultanate (1833–1899)

Jambi Sultanate (1833–1899)- Kuala (1886–1946)

Pelalawan (1859 – November 1945)

Pelalawan (1859 – November 1945)- Siantar (1904–1946)

- Tanah Jawa (1904–1946)

Lingga-Riau (1819–1911)

Lingga-Riau (1819–1911)

Banten (1682–1811)

Banten (1682–1811) Cirebon (1684–1819)

Cirebon (1684–1819) Yogjakarta Sultanate (13 February 1755 – 1942)

Yogjakarta Sultanate (13 February 1755 – 1942) Mataram Sultanate (later Surakarta Sunanate) (26 February 1677 – 19 August 1945)

Mataram Sultanate (later Surakarta Sunanate) (26 February 1677 – 19 August 1945) Principality of Mangkunegara (24 February 1757 – 1946)

Principality of Mangkunegara (24 February 1757 – 1946) Duchy of Pakualaman (22 June 1812 – 1942)

Duchy of Pakualaman (22 June 1812 – 1942)- Semarang (1682–1809)

Klungkung (1843–1908)

Klungkung (1843–1908) Badung (1843–1906)

Badung (1843–1906)- Bangli (1843–1908)

- Buleleng (1841–1872 and 1890–1893)

- Gianyar (1843–1908)

- Jembrana (1849–1882)

Karang Asem (1843–1908)

Karang Asem (1843–1908)- Tabanan (1843–1906)

- Banjarmasin (1787–1860)

- Pontianak Sultanate (16 August 1819 – 1942)

- Sambas Sultanate (1819–1949)

- Kubu (4 June 1823 – 1949)

- Landak (1819–c. 1949)

- Mempawah Kingdom (1819–1942)

- Sanggau Kingdom (182?–1949)

- Sekadau (182?–c. 1949)

- Simpang (1822–c. 1949)

- Sintang (1822–1949)

- Sukadana (1828–c.1949)

- Kota Waringin Sultanate (1824–1949)

- Kutai Kertanegara Sultanate (8 August 1825 – 1949)

- Gunung Tabur (1844–c.1945)

- Bulungan Sultanate (1844–c.1949)

- Simbaliung (1844–c. 1949)

- Kubu (1823–1949)

- Tayan (1823–c. 1949)

- Gowa Sultanate (1669–1906; 1936–1949)

- Bone Sultanate (1669–1905)

- Bolaang Mongonduw (1825–c. 1949)

- Laiwui (1858–c. 1949)

- Luwu (1861–c. 1949)

- Soppeng (1860–c. 1949)

- Butung (1824–c. 1949)

- Siau (1680–c. 1949)

- Banggai (1907–c. 1949)

- Tallo (1668–1780)

- Wajo (1860–c. 1949)

- Tabukan (1677–c. 1949)

Ajattappareng Confederacy (1905–c. 1949)

[edit]- Malusetasi

- Rapang

- Swaito (union of Sawito and Alita, 1908)

- Sidenreng

- Supa

Mabbatupappeng Confederacy (1906–c. 1949)

[edit]Mandar Confederacy (1906–c. 1949)

[edit]Massenrempulu Confederacy (1905–c. 1949)

[edit]- Ternate Sultanate (12 October 1676 – 1949)

- Bacan Sultanate (1667–1949)

- Tidore (1657–c.1949)

West Timor and Alor

[edit]- Amanatun (1749–c. 1949)

- Amanuban (1749–c. 1949)

- Amarasi (1749–c. 1949)

- Amfoan (1683–c. 1949)

- Beboki (1756–c. 1949)

- Belu (1756–c.1949)

- Insana (1756–c.1949)

- Sonbai Besar (1756–1906)

- Sonbai Kecil (1659–1917)

- Roti (Korbafo before 1928) (c. 1750–c.1949)

- TaEbenu (1688–1917)

Dutch New Guinea:

Dutch New Guinea:

Kaimana Sultanate (1828-1949)

Kaimana Sultanate (1828-1949)

France's protectorates and protected states

[edit]Africa

[edit]"Protection" was the formal legal structure under which French colonial forces expanded in Africa between the 1830s and 1900. Almost every pre-existing state that was later part of French West Africa was placed under protectorate status at some point, although direct rule gradually replaced protectorate agreements. Formal ruling structures, or fictive recreations of them, were largely retained—as with the low-level authority figures in the French Cercles—with leaders appointed and removed by French officials.[38]

- Benin traditional states

- Independent of

Danhome, under French protectorate, from 1889

Danhome, under French protectorate, from 1889 - Porto-Novo a French protectorate, 23 February 1863 – 2 January 1865. Cotonou a French Protectorate, 19 May 1868. Porto-Novo French protectorate, 14 April 1882.

- Independent of

- Central African Republic traditional states:

- French protectorate over Dar al-Kuti (1912 Sultanate suppressed by the French), 12 December 1897

- French protectorate over the Sultanate of Bangassou, 1894

- Burkina Faso was from 20 February 1895 a French protectorate named Upper Volta (Haute-Volta)

- Chad: Baghirmi state 20 September 1897 a French protectorate

- Côte d'Ivoire: 10 January 1889 French protectorate of Ivory Coast

- Guinea: 5 August 1849 French protectorate over coastal region; (Riviéres du Sud).

- Niger, Sultanate of Damagaram (Zinder), 30 July 1899 under French protectorate over the native rulers, titled Sarkin Damagaram or Sultan

- Senegal: 4 February 1850 First of several French protectorate treaties with local rulers

- Comoros: 21 April 1886 French protectorate (Anjouan) until 25 July 1912 when annexed.

- Present Djibouti was originally, from 24 June 1884, the Territory of Obock and Protectorate of Tadjoura (Territoires Français d'Obock, Tadjoura, Dankils et Somalis), a French protectorate recognized by Britain on 9 February 1888, renamed on 20 May 1896 as French Somaliland (Côte Française des Somalis).

- Mauritania: 12 May 1903 French protectorate; within Mauritania several traditional states:

- Adrar emirate from 9 January 1909 French protectorate (before Spanish)

- The Taganit confederation's emirate (founded by Idaw `Ish dynasty), from 1905 under French protectorate.

- Brakna confederation's emirate

- Emirate of Trarza: 15 December 1902 placed under French protectorate status.

Morocco – most of the sultanate was under French protectorate (30 March 1912 – 7 April 1956) although, in theory, it remained a sovereign state under the Treaty of Fez;[39] this[which?] fact was confirmed by the International Court of Justice in 1952.[40]

Morocco – most of the sultanate was under French protectorate (30 March 1912 – 7 April 1956) although, in theory, it remained a sovereign state under the Treaty of Fez;[39] this[which?] fact was confirmed by the International Court of Justice in 1952.[40]

- The northern part of Morocco was under Spanish protectorate in the same period.

- Traditional Madagascar States

Kingdom of Imerina under French protectorate, 6 August 1896. French Madagascar colony, 28 February 1897.

Kingdom of Imerina under French protectorate, 6 August 1896. French Madagascar colony, 28 February 1897.

Tunisia (12 May 1881 – 20 March 1956): became a French protectorate by treaty

Tunisia (12 May 1881 – 20 March 1956): became a French protectorate by treaty

Americas

[edit] Second Mexican Empire (1863–1867), established by Emperor Napoleon III during the Second French intervention in Mexico and ruled by the Austrian-born, French puppet monarch Maximilian I

Second Mexican Empire (1863–1867), established by Emperor Napoleon III during the Second French intervention in Mexico and ruled by the Austrian-born, French puppet monarch Maximilian I

Asia

[edit]

- French Indochina until 1953/54:

Europe

[edit] Rhenish Republic (1923–1924)

Rhenish Republic (1923–1924) Saar Protectorate (1946–1956), not colonial or amical, but a former part of Germany that would by referendum return to it, in fact a re-edition of a former League of Nations mandate. Most French protectorates were colonial.

Saar Protectorate (1946–1956), not colonial or amical, but a former part of Germany that would by referendum return to it, in fact a re-edition of a former League of Nations mandate. Most French protectorates were colonial.

Oceania

[edit] French Polynesia, mainly the Society Islands (several others were immediately annexed).[41] All eventually were annexed by 1889.

French Polynesia, mainly the Society Islands (several others were immediately annexed).[41] All eventually were annexed by 1889.

Otaheiti (native king styled Ari`i rahi) becomes a French protectorate known as Tahiti, 1842–1880

Otaheiti (native king styled Ari`i rahi) becomes a French protectorate known as Tahiti, 1842–1880 Raiatea and Tahaa (after temporary annexation by Otaheiti; (title Ari`i) a French protectorate, 1880)

Raiatea and Tahaa (after temporary annexation by Otaheiti; (title Ari`i) a French protectorate, 1880) Mangareva (one of the Gambier Islands; ruler title `Akariki) a French protectorate, 16 February 1844 (unratified) and 30 November 1871[42]

Mangareva (one of the Gambier Islands; ruler title `Akariki) a French protectorate, 16 February 1844 (unratified) and 30 November 1871[42]

Wallis and Futuna:

Wallis and Futuna:

Germany's protectorates and protected states

[edit]

The German Empire used the word Schutzgebiet, literally protectorate, for all of its colonial possessions until they were lost during World War I, regardless of the actual level of government control. Cases involving indirect rule included:

German New Guinea (1884–1920), now part of Papua New Guinea

German New Guinea (1884–1920), now part of Papua New Guinea German South West Africa (1884–1920), present-day Namibia

German South West Africa (1884–1920), present-day Namibia Togoland (1884–1914), now part of Ghana and Togo

Togoland (1884–1914), now part of Ghana and Togo North Solomon Islands (1885–1920), now part of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands

North Solomon Islands (1885–1920), now part of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands Wituland (1885–1890), now part of Kenya

Wituland (1885–1890), now part of Kenya Ruanda-Urundi (1894–1920)

Ruanda-Urundi (1894–1920) German Samoa (1900–1920), present-day Samoa

German Samoa (1900–1920), present-day Samoa Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Nauru, various officials posted with the Head Chiefs

Nauru, various officials posted with the Head Chiefs Gando Emirate (1895–1897)[43]

Gando Emirate (1895–1897)[43] Gulmu (1895–1897)[43]

Gulmu (1895–1897)[43]

Before and during World War II, Nazi Germany designated the rump of occupied Czechoslovakia and Denmark as protectorates:

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (1939–1945), however it was also considered a partially annexed territory of Germany

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (1939–1945), however it was also considered a partially annexed territory of Germany Denmark (1940–1943)

Denmark (1940–1943)

India's protectorates

[edit] Bhutan (1947–2007).

Bhutan (1947–2007). Kingdom of Sikkim (1950–1975), later acceded to India as State of Sikkim.[44]

Kingdom of Sikkim (1950–1975), later acceded to India as State of Sikkim.[44] Cis-Sutlej states[45][46] (1809–1862)

Cis-Sutlej states[45][46] (1809–1862) Kingdom of Nepal (1816–1923; protected state)[14]

Kingdom of Nepal (1816–1923; protected state)[14] Kingdom of Sikkim (1861–1947), (1947–1972)[47]

Kingdom of Sikkim (1861–1947), (1947–1972)[47] Maldive Islands (1776–1965, 1965–1968, 1968–1990)[24]

Maldive Islands (1776–1965, 1965–1968, 1968–1990)[24]- Various British Raj princely states (1845–1947)

Bhutan (1906–1947 and 1948; protected state)[14]

Bhutan (1906–1947 and 1948; protected state)[14]- Ancient India

- Indian empires

- British Raj

- List of Indian Princely States

Italy's protectorates and protected states

[edit] The Albanian Republic (1917–1920) and the

The Albanian Republic (1917–1920) and the  Albanian Kingdom (1939–1943)

Albanian Kingdom (1939–1943) Monaco under amical Protectorate of the Kingdom of Sardinia 20 November 1815 to 1860.

Monaco under amical Protectorate of the Kingdom of Sardinia 20 November 1815 to 1860. Ethiopia : 2 May 1889 Treaty of Wuchale, in the Italian language version, stated that Ethiopia was to become an Italian protectorate, while the Ethiopian Amharic language version merely stated that the Emperor could, if he so chose, go through Italy to conduct foreign affairs. When the differences in the versions came to light, Emperor Menelik II abrogated first the article in question (XVII), and later the whole treaty. The event culminated in the First Italo-Ethiopian War, in which Ethiopia was victorious and defended her sovereignty in 1896.

Ethiopia : 2 May 1889 Treaty of Wuchale, in the Italian language version, stated that Ethiopia was to become an Italian protectorate, while the Ethiopian Amharic language version merely stated that the Emperor could, if he so chose, go through Italy to conduct foreign affairs. When the differences in the versions came to light, Emperor Menelik II abrogated first the article in question (XVII), and later the whole treaty. The event culminated in the First Italo-Ethiopian War, in which Ethiopia was victorious and defended her sovereignty in 1896. Libya: on 15 October 1912 Italian protectorate declared over Cirenaica (Cyrenaica) until 17 May 1919.

Libya: on 15 October 1912 Italian protectorate declared over Cirenaica (Cyrenaica) until 17 May 1919. Benadir Coast in Somalia: 3 August 1889 Italian protectorate (in the northeast; unoccupied until May 1893), until 16 March 1905 when it changed to

Benadir Coast in Somalia: 3 August 1889 Italian protectorate (in the northeast; unoccupied until May 1893), until 16 March 1905 when it changed to  Italian Somaliland.

Italian Somaliland.

Majeerteen Sultanate since 7 April 1889 under Italian protectorate (renewed 7 April 1895), then in 1927 incorporated into the Italian colony.

Majeerteen Sultanate since 7 April 1889 under Italian protectorate (renewed 7 April 1895), then in 1927 incorporated into the Italian colony. Sultanate of Hobyo since December 1888 under Italian protectorate (renewed 11 April 1895), then in October 1925 incorporated into the Italian colony (known as Obbia).

Sultanate of Hobyo since December 1888 under Italian protectorate (renewed 11 April 1895), then in October 1925 incorporated into the Italian colony (known as Obbia).

Puntland Protectorate italy

Puntland Protectorate italy

Former colonies, protectorates and occupied areas

[edit]

- Italian Eritrea (1882–1947)

- Italian Somalia (1889–1947)

- Oltre Giuba (1924-1926)

- Trust Territory of Somaliland (1950–1960)

- Libya (1911–1947)

- Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica (1911–1934)

- Italian Libya (1934–1943)

- Trans-Juba (1924–1926)

- Italian East Africa (1936–1941)

- Italian Ethiopia (1936–1941)

- Italian concessions in China

- Italian concession of Tientsin (1901–1943)

- Italian Albania (1917–1920, 1939–1943)

- Italian Islands of the Aegean (1912–1947)

- Italian occupation of France (1940–1943)

- Italian occupation of Corsica (1942-1943)

- Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945)

- Italian occupation of Montenegro (1941–1943)

- Hellenic State (1941–1943)

- Tunisia (1942–1943)

Protectorate Additional proposals

[edit]

In the 1940s, De Vecchi contemplated an "Imperial Italy" stretching from Europe to North Africa, made of the "Imperial Italy" (with an enlarged Italian Empire in eastern Africa, from the Egyptian shores on the Mediterranean to Somalia).

He dreamt of a powerful Italy enlarged:

- 1) in Europe, from Nice to the Governatorato di Dalmazia in Dalmatia and possibly Greater Albania (see map Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine), the Ionian islands, the Principality of Pindus in Epirus (northern Greece), the Dodecanese.

- 2) in northern coastal Africa, from Tunisia to Libya (the Fezzan of Libya was to be considered a colony of the empire).

In a hopeful peace negotiation following an Axis victory, Mussolini had planned to acquire for his Imperial Italy the full island of Crete (that was mostly German occupied) and the surrounding southern Greek islands, connecting the Italian Dodecanese possessions to the already Italian Ionian islands.[48][page needed]

South of the Fourth Shore, some fascist leaders dreamt of an Italian Empire that, starting in the Fezzan, would include Egypt, Sudan and reach Italian East Africa.[49]

The Allied victory in the Second World War ended these projects and terminated all fascist ambitions for the empire.

Finally, in 1947 the Italian Republic formally relinquished sovereignty over all its overseas colonial possessions as a result of the Treaty of Peace with Italy. There were discussions to maintain Tripolitania (a province of Italian Libya) as the last Italian colony, but they were not successful.

In November 1949, the former Italian Somaliland, then under British military administration, was made a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration for a period of 10 years. On 1 July 1960, the Trust Territory of Somalia merged with British Somaliland to form the independent Somali Republic.

Japan's protectorates

[edit]Japan's protectorates

This is a list of regions occupied or annexed by the Empire of Japan until 1945, the year of the end of World War II in Asia, after the surrender of Japan. Control over all territories except most of the Japanese mainland (Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and some 6,000 small surrounding islands) was renounced by Japan in the unconditional surrender after World War II and the Treaty of San Francisco. A number of territories occupied by the United States after 1945 were returned to Japan, but there are still a number of disputed territories between Japan and Russia (the Kuril Islands dispute), South Korea and North Korea (the Liancourt Rocks dispute), the People's Republic of China and Taiwan (the Senkaku Islands dispute).

Japan:

Japan:

Manchuria (Manchukuo), Northern China (1945/1946)

Manchuria (Manchukuo), Northern China (1945/1946) Philippines (1945/1946)

Philippines (1945/1946) Burma (1945/1948)

Burma (1945/1948) North Korea (1945/1948)

North Korea (1945/1948) South Korea (1945/1948)

South Korea (1945/1948) Taiwan (1945/1949)

Taiwan (1945/1949) Malaysia

Malaysia Singapore (1965)

Singapore (1965) Taiwan (1642)

Taiwan (1642) Indonesia (1945/1949)

Indonesia (1945/1949) Netherlands New Guinea (1962)

Netherlands New Guinea (1962)

Korean Empire (1905–1910)

Korean Empire (1905–1910) Manchukuo (1932–1945)

Manchukuo (1932–1945) Mengjiang (1939–1945)

Mengjiang (1939–1945)

World War II

[edit]| Territory | Japanese name | Date | Population est. (1944) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Sakhalin | Karafuto Prefecture (樺太庁) | 1905–1943 | 406,000 | Elevated to naichi status in 1943. |

| Mainland China | Chūgoku tairiku (中国大陸) | 1931–1945 | 200,000,000 (est.) | Manchukuo 50 million (1940), Rehe, Kwantung Leased Territory, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Shandong, Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, plus parts of : Guangdong, Guangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Fujian, Guizhou, Inner Mongolia |

| Japan proper | naichi (内地) | 1868–1945 | 76,200,000 | Present day Japan, South Sakhalin (after 1943), and Kuril Islands |

| Korea | Chōsen (朝鮮) | 1910–1945 | 25,500,000 | |

| Taiwan | Taiwan (臺灣) | 1895–1945 | 6,586,000 | |

| Hong Kong | Hon Kon (香港) | December 12, 1941 – August 15, 1945 | 1,400,000 | Hong Kong (UK) |

| :: East Asia (subtotal) | Higashi Ajia (東アジア) | – | 310,092,000 | |

| Vietnam | Annan (安南) | July 15, 1940 – August 29, 1945 | 22,122,000 | As French Indochina (FR) |

| Cambodia | Kanbojia (カンボジア) | July 15, 1940 – August 29, 1945 | 3,100,000 | As French Indochina, Japanese occupation of Cambodia |

| Laos | Raosu (ラオス) | July 15, 1940 – August 29, 1945 | 1,400,000 | As French Indochina, Japanese occupation of Laos |

| Thailand | Tai (タイ) | December 8, 1941 – August 15, 1945 | 16,216,000 | Independent state but allied with Japan |

| Malaysia | Maraya (マラヤ), Kita Boruneo (北ボルネオ), Marai (マライ) | March 27, 1942 – September 6, 1945 (Malaya), March 29, 1942 – September 9, 1945 (Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan, North Borneo) | 4,938,000 plus 39,000 (Brunei) | As Malaya (UK), British Borneo (UK), Brunei (UK) |

| Philippines | Firipin (フィリピン) | May 8, 1942 – July 5, 1945 | 17,419,000 | Philippines (US) |

| Dutch East Indies | Higashi Indo (東印度), Sumatora Nishikaigan (スマトラ西海岸) | January 18, 1942 – October 21, 1945 | 72,146,000 | Dutch East Indies (NL), West Coast Sumatra (NL) |

| Singapore | Syōnan-tō (昭南島) | February 15, 1942 – September 9, 1945 | 795,000 | Singapore (UK) |

| Burma (Myanmar) | Biruma (ビルマ) | 1942–1945 | 16,800,000 | Burma (UK) |

| East Timor | Higashi Chimōru (東チモール) | February 19, 1942 – September 2, 1945 | 450,000 | Portuguese Timor (PT) |

| :: Southeast Asia (subtotal) | Tōnan Ajia (東南アジア) | – | 155,452,000 | |

| New Guinea | Nyū Ginia (ニューギニア) | December 27, 1941 – September 15, 1945 | 1,400,000 | As Papua and New Guinea (AU) |

| Guam | Ōmiya-tō (大宮島) | January 6, 1942 – October 24, 1945 | from Guam (US) | |

| South Seas Mandate | Nan'yō Guntō (南洋群島) | 1919–1945 | 129,000 | from German Empire |

| Nauru | Nauru (ナウル) | August 26, 1942 – September 13, 1945 | 3,000 | Occupied from the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand |

| Wake Island, US | Ōtori-shima, -jima (大鳥島) | December 27, 1941 – September 4, 1945 | nil | US |

| Kiribati | Kiribasu (キリバス) | December 1941 – January 22, 1944 | 28,000 | from Gilbert Islands (UK) |

| :: Pacific Islands (subtotal) | – | – | 1,433,000 | |

| :: Total Population | – | – | 465,544,000 |

Disclaimer: Not all areas were considered part of Imperial Japan but rather part of puppet states & sphere of influence, allies, included separately for demographic purposes. Sources: POPULSTAT Asia

Other occupied islands during World War II:

- Andaman Islands (India) – March 29, 1942 – September 9, 1945

- Christmas Island (Australia) – March 1942 – October 1945

- Attu and Kiska (Alaska, United States) – June 3, 1942 – August 15, 1943

Areas attacked but not conquered

[edit]- Kohima and Manipur (India)

- Dornod (Khalkhin Gol, Mongolia)

- Midway Atoll (United States)

Raided without immediate intent of occupation

[edit]- Air raids

- Pearl Harbor (Hawaii, United States)

- Colombo and Trincomalee (Sri Lanka)

- Calcutta (India)

- Chittagong (Bangladesh)

- Air raids on Australia, including:

- Broome (Western Australia, Australia)

- Darwin (Northern Territory, Australia)

- Townsville (Queensland, Australia)

- Dutch Harbor (Alaska, United States)

- Lookout Air Raids (Oregon, United States)

- Naval bombardment by submarine

- British Columbia (Canada)

- Ellwood (Santa Barbara, California, United States)

- Fort Stevens (Oregon, United States)

- Newcastle (New South Wales, Australia)

- Gregory (Western Australia, Australia)

- Midget sub attack

- Sydney (New South Wales, Australia)

- Diego Suarez (Madagascar)

Poland's protectorates

[edit] Kaffa (1462–1475)

Kaffa (1462–1475)

Portugal's protectorates

[edit]- Cabinda (Portuguese Congo) (1885–1974), Portugal first claimed sovereignty over Cabinda in the February 1885 Treaty of Simulambuco, which gave Cabinda the status of a protectorate of the Portuguese Crown under the request of "the princes and governors of Cabinda".

- Kingdom of Kongo (1857–1914)

- Gaza Empire (1824–1895), now part of Mozambique

- Angoche Sultanate (1903–1910)

- Kingdom of Larantuka (1515–1859)

- Portuguese Angola (now Angola)

- Mainland Angola

- Portuguese Congo(now Cabinda Province of Angola)

- Portuguese Mozambique(now Mozambique)

- Portuguese Guinea(now Guinea-Bissau)

- Portuguese Gold Coast now part of Ghana

- Portuguese Cape Verde

- Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe

- Ajuda (Whydah, in Benin)

- Portuguese Angola

- Annobón

- Cabinda

- Cape Verde (Cabo Verde)

- Ceuta

- Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá

- Gorée (in Senegal)

- Malindi

- Mombasa

- Algarve Ultramar (Morocco)

- Nigeria (Lagos area)

- Mozambique

- Portuguese Gold Coast (settlements along coast of Ghana)

- Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau)

- Quíloa

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- Tangier

- Zanzibar

- Ziguinchor

Russia's and the Soviet Union's protectorates and protected states

[edit]Russian

[edit]

- Fort Ross

- Russian America

- Russian concession of Tianjin

- Russian Dalian

- Sagallo

Cossack Hetmanate (1654–1764)

Cossack Hetmanate (1654–1764) Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (1783–1801)

Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (1783–1801) Kingdom of Imereti (1804–1810)

Kingdom of Imereti (1804–1810) Revolutionary Serbia (1807–1812)

Revolutionary Serbia (1807–1812) Principality of Serbia (1826–1856), now part of Serbia

Principality of Serbia (1826–1856), now part of Serbia Principality of Moldova (1829–1856), now part of Moldova, Romania and Ukraine

Principality of Moldova (1829–1856), now part of Moldova, Romania and Ukraine Principality of Wallachia (1829–1856)

Principality of Wallachia (1829–1856) Emirate of Bukhara (1873–1920)

Emirate of Bukhara (1873–1920) Khanate of Khiva (1873–1920)

Khanate of Khiva (1873–1920) Uryankhay Krai (1914)

Uryankhay Krai (1914) Second East Turkestan Republic (1944–1949), now part of Xinjiang, China

Second East Turkestan Republic (1944–1949), now part of Xinjiang, China

De facto

[edit]Some sources mention the following territories as de facto Russian protectorates:

South Ossetia (2008–present)[50]

South Ossetia (2008–present)[50] Transnistria (1992–present)[51]

Transnistria (1992–present)[51] Abkhazia (1994–present)[50]

Abkhazia (1994–present)[50] Donetsk People's Republic (2015–2022)[52]

Donetsk People's Republic (2015–2022)[52] Luhansk People's Republic (2015–2022)[53]

Luhansk People's Republic (2015–2022)[53] Republic of Artsakh (2020–2023)[54][55][56]

Republic of Artsakh (2020–2023)[54][55][56]

Spain's protectorates

[edit] Spanish Morocco protectorate from 27 November 1912 until 2 April 1958 (Northern zone until 7 April 1956, Southern zone (Cape Juby) until 2 April 1958).

Spanish Morocco protectorate from 27 November 1912 until 2 April 1958 (Northern zone until 7 April 1956, Southern zone (Cape Juby) until 2 April 1958). Sultanate of Sulu (1851–1899)

Sultanate of Sulu (1851–1899)

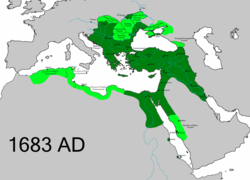

Turkey's and the Ottoman Empire's protectorates and protected states

[edit] Aceh Sultanate (1569–1903)

Aceh Sultanate (1569–1903) Maldives (1560–1590)

Maldives (1560–1590) Cossack Hetmanate (1669–1685)

Cossack Hetmanate (1669–1685)

De facto

[edit] Northern Cyprus (1983–present)

Northern Cyprus (1983–present)

Ottoman (Turkish)

[edit]

- Sultanate of Aceh (1569–1903)

- Yettishar (1873–1877)

- Maldives

- Rumelia

- Ottoman North Africa

- Ottoman Northeast Africa

- Ottoman Arabia

- Sharifate of Mecca (1517–1783/1818–1916)

- Ottoman Hejaz

- Ottoman Lahsa

- Ottoman Najd

- Ottoman Yemen

- Ottoman Serbia

- Ottoman Bulgaria

- Ottoman Bosnia

- Ottoman Albania

- Ottoman Hungary

- Ottoman Greece

- Ottoman North Macedonia

- Ottoman Montenegro

- Crimean Khanate (1475–1774)

United Nations' protectorates

[edit]List

[edit]Current

[edit]| Name | Location | Years | Today part of |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) | United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus (UNBZC) | 1964–present | |

| United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) | UNDOF Zone on the Golan Heights | 1974–present | |

| United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) | United Nations Administered Kosovo | 1999–present (only de jure since 2008) |

(claimed by |

Former

[edit]| Name | Location | Years | Today part of |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) | Western New Guinea | 1962–1963 | |

| United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) | Cambodia | 1992–1993 | |

| United Nations Transitional Administration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) | Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia | 1996–1998 | |

| United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) | United Nations Administered East Timor | 1999–2002 |

Proposed trust territories

[edit]- Jerusalem: Under the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, Jerusalem would have become a corpus separatum territory under United Nations Trusteeship Council administration. Both Palestinian Arabs and the Yishuv opposed this solution.

- Korea: In wartime talks, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed that Korea be placed under an American–Soviet trust administration. The plan was eclipsed after Roosevelt's death on 12 April 1945, although it was expressed in the December Moscow Conference, and caused considerable civil unrest in Korea.[59]

- Vietnam: Roosevelt also proposed that French Indochina be placed under an international trusteeship as an alternative to French colonial rule and immediate independence.[60]

- Italian Libya: Between 1945 and 1947, the Soviet Union made various proposals that Tripolitania be placed under Soviet trusteeship for ten years, or a joint trusteeship with the United Kingdom and the United States, or that Libya as a whole become an Italian trusteeship.[61]

- Mandatory Palestine: The United States government under Harry Truman proposed a UN trusteeship status for the Mandatory Palestine in 1948.[62][63]

- Ryukyu Islands and Bonin Islands: the Treaty of San Francisco included provisions which provided the United States the right to convert its administration over the Ryukyu and Bonin Islands into a trust territory, but it never did so before sovereignty was voluntarily reverted to Japan.[64]

United States' protectorates and protected states

[edit]After becoming independent nations in 1902 and 1903 respectively, Cuba and Panama became protectorates of the United States. In 1903, Cuba and the US signed the Cuban–American Treaty of Relations, which affirmed the provisions of the Platt Amendment, including that the US had the right to intervene in Cuba to preserve its independence, among other reasons (the Platt Amendment had also been integrated into the 1901 constitution of Cuba). Later that year, Panama and the US signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which established the Panama Canal Zone and gave the US the right to intervene in the cities of Panama and Colón (and the adjacent territories and harbors) for the maintenance of public order. The 1904 constitution of Panama, in Article 136, also gave the US the right to intervene in any part of Panama "to reestablish public peace and constitutional order." Haiti later also became a protectorate after the ratification of the Haitian–American Convention (which gave the US the right to intervene in Haiti for a period of ten years, which was later expanded to twenty years through an additional agreement in 1917) on September 16, 1915.

The US also attempted to establish protectorates over the Dominican Republic[65] and Nicaragua through the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty.

De facto

[edit] Republic of Negros (1899–1901)[68]

Republic of Negros (1899–1901)[68] Republic of Zamboanga (1899–1903)

Republic of Zamboanga (1899–1903) Sultanate of Sulu (1899–1915)

Sultanate of Sulu (1899–1915)

United States' protectorates and protected states Former insular areas

[edit] Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: U.N. trust territory administered by the U.S.; included the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: U.N. trust territory administered by the U.S.; included the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Philippines: military government, 1899–1902; insular government, 1902–1935; commonwealth government, 1935–1942 and 1945–1946 (islands under Japanese occupation, 1942–1945 and puppet state, 1943–1945); granted independence on July 4, 1946, by the Treaty of Manila.

Philippines: military government, 1899–1902; insular government, 1902–1935; commonwealth government, 1935–1942 and 1945–1946 (islands under Japanese occupation, 1942–1945 and puppet state, 1943–1945); granted independence on July 4, 1946, by the Treaty of Manila. Puerto Rico: military government, 1899–1900; insular government, 1900–1952; became a commonwealth on July 25, 1952.[69]

Puerto Rico: military government, 1899–1900; insular government, 1900–1952; became a commonwealth on July 25, 1952.[69] Guam: naval government, 1899–1941 and 1944–50 (island under Japanese occupation, 1941–1944); territory organized and civil government established by the Guam Organic Act of 1950.

Guam: naval government, 1899–1941 and 1944–50 (island under Japanese occupation, 1941–1944); territory organized and civil government established by the Guam Organic Act of 1950. Hawaii: republic government, 1898–1900; territorial government, 1900–1959; became the State of Hawaii and the incorporated, unorganized territory of Palmyra Atoll on August 21, 1959.[70][71]

Hawaii: republic government, 1898–1900; territorial government, 1900–1959; became the State of Hawaii and the incorporated, unorganized territory of Palmyra Atoll on August 21, 1959.[70][71]- Swan Islands (1863–1972): claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; sovereignty ceded to Honduras in a 1972 treaty.[72]

- Serrana Bank and Roncador Bank: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claims ceded to Colombia.

- Quita Sueño Bank: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claim relinquished in treaty with Colombia.

- Caroline Island, Kirimati, Flint Island, Malden Island, Starbuck Island, Vostok Island, Birnie Island, Gardner Island, Orona, McKean Island, Manra, Rawaki, Canton Island and Enderbury Island: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claims ceded to Kiribati.

- Funafuti, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae and Niulakita: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claims ceded to Tuvalu.

- Pukapuka, Manihiki, Penrhyn and Rakahanga: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claims ceded to the Cook Islands.

- Atafu, Fakaofo and Nukunonu: claimed by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act; claims ceded to Tokelau.

Contemporary usage by the United States

[edit]Some agencies of the United States government, such as the Environmental Protection Agency, refer to the District of Columbia and insular areas of the United States—such as American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands—as protectorates.[73] However, the agency responsible for the administration of those areas, the Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) within the United States Department of Interior, uses only the term "insular area" rather than protectorate.

Colonies by American (continent) countries

[edit]American

[edit]

- American Concession in Tianjin (1869–1902)

- American Concession in Shanghai (1848–1863)

- American Concession in Beihai (1876–1943)

- American Concession in Harbin (1898–1943)

- American Samoa

- Beijing Legation Quarter (1861–1945)

- Corn Islands (1914–1971)

- Canton and Enderbury Islands

- Caroline Islands

- Cuba (Platt Amendment turned Cuba into a protectorate – until Cuban Revolution)

- Falkland Islands (1832)

- Guantánamo Bay

- Guam

- Gulangyu Island (1903–1945)

- Haiti (1915–1934)

- Hawaii

- Indian Territory (1834–1907)

- Isle of Pines (1899–1925)

- Liberia (Independent since 1847, US protectorate until post-WW2)

- Mexico City (1847)

- Midway

- Nicaragua (1912–1933)

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Palau

- Palmyra Atoll

- Panama (Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty turned Panama into a protectorate, protectorate until post-WW2)

- Panama Canal Zone (1903–1979)

- Philippines (1898–1946)

- Puerto Rico

- Veracruz

- Quita Sueño Bank (1869–1981)

- Roncador Bank (1856–1981)

- Ryukyu Islands

- Russian Far East

- Shanghai International Settlement (1863–1945)

- Sultanate of Sulu (1903–1915)

- Swan Islands, Honduras (1914–1972)

- Tangier International Zone (Now present-day Tangier, Morocco) (1924–1956)

- Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

- United States Virgin Islands

- Wake Island

- Wilkes Land

- Californias

- Central America

- Chiapas

- Clipperton Island

- Revillagigedo Islands

- Texas

- Manila

- Guatemalan

- Belize

- Chiapas

- Ecuadorian

- Galápagos Islands

- Tumbes

- Jaén

- Maynas

- Colombian

- Panama

- Ecuador

- Venezuela

- Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina

- Mosquito Coast

- Venezuelan

- Western part of Guyana

- Argentine

- Argentine Antarctica

- Asuncion (1873)

- California (1818)

- Chile (1817–1818 during the Chilean war of independence)

- Equatorial Guinea (1810–1815)[74]

- Falkland Islands and Dependencies (1829–1831, 1832–1833, 1982)

- Formosa

- Gobierno del Cerrito (1843–1851)

- Gonaïves, Haití.[75]

- Misiones

- Paraguay (1873)

- Patagonia

- Peru (1820–1822 during the Independence of Peru)

- Puna de Atacama (1839– )

- Tierra del Fuego

- Uruguay (Cisplatine War)

- Paraguayan

- Mato Grosso do Sul

- Formosa

- Eastern Salta

- Misiones

- Southwestern Paraná

- Peruvian

- Arica

- Tarapacá

- Acre

- Bolivian

- Puna de Atacama (1825–1839 ceded to Argentina) (1825–1879 ceded to Chile)

- Atacama

- Salta

- Jujuy

- Western Catamarca

- Acre

- Chilean

- Patagonia

- Tierra del Fuego

- Easter Island

- Brazilian

- Uruguay

- Acre

- Cape Verde (Occupied for two years after independence)

- Angola (During the Angolan war of independence)

- Mozambique (During the Mozambican war of independence)

- Asuncion

- Brazilian Antarctica

Gained independence from the United States

[edit]1898-1965

[edit]| Country | Event name | Colonial power | Independence date | First head of state | Part of war(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santo Domingo Affair | February 11, 1904 | Juan Isidro Jiminez | Banana Wars | ||

| United States occupation of Haiti | August 1, 1934 | Sténio Vincent | Banana Wars | ||

| United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) | September 18, 1924 | Desiderio Arias | Banana Wars | ||

| Dominican Civil War | September 3, 1965 | Joaquín Balaguer | Cold War |

1907–1919 (miscellaneous)

[edit]| Occupied territory | Years | Occupied state | Occupying state | Event | Part of war(s) | Subsequently annexed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicaragua | 1912–1933 | Occupation of Nicaragua | Banana Wars | No | ||

| Veracruz | 1914 | Occupation of Veracruz | Mexican Revolution | No |

World War I and immediate aftermath

[edit]| Occupied territory | Years | Occupied state | Occupying state | Event | Part of war(s) | Subsequently annexed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haiti | 1915–1934 | Occupation of Haiti | Banana Wars | No | ||

| Dominican Republic | 1916–1924 | Occupation of the Dominican Republic | No | |||

| Cuba | 1917–1922 | Sugar Intervention | No |

1960–1979

[edit]| Occupied territory | Years | Occupied state | Occupying state | Event | Part of war(s) | Subsequently annexed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominican Republic | 1965–1966 | Invasion of the Dominican Republic | Dominican Civil War | No |

1980–1999

[edit]| Occupied territory | Years | Occupied state | Occupying state | Event | Part of war(s) | Subsequently annexed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falkland Islands | 1982 | Occupation of the Falkland Islands | Falklands War | No | ||

| Grenada | 1983 | Invasion of Grenada | Grenadian Revolution | No | ||

| Panama | 1989–1990 | Invasion of Panama | War on drugs | No | ||

| Haiti | 1994–1995 | Operation Uphold Democracy | 1991 Haitian coup d'état | No |

Joint protectorates

[edit] Republic of Ragusa (1684–1798), a joint Habsburg Austrian–Ottoman Turkish protectorate

Republic of Ragusa (1684–1798), a joint Habsburg Austrian–Ottoman Turkish protectorate- The

United States of the Ionian Islands and the

United States of the Ionian Islands and the  Septinsular Republic were federal republics of seven formerly Venetian (see Provveditore) Ionian Islands (Corfu, Cephalonia, Zante, Santa Maura, Ithaca, Cerigo, and Paxos), officially under joint protectorate of the allied Christian powers, de facto a British amical protectorate from 1815 to 1864.

Septinsular Republic were federal republics of seven formerly Venetian (see Provveditore) Ionian Islands (Corfu, Cephalonia, Zante, Santa Maura, Ithaca, Cerigo, and Paxos), officially under joint protectorate of the allied Christian powers, de facto a British amical protectorate from 1815 to 1864.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956)

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956) Independent State of Croatia (1941–1943)

Independent State of Croatia (1941–1943) Allied-occupied Germany (1945–1949)

Allied-occupied Germany (1945–1949) Allied-occupied Austria (1945–1955)

Allied-occupied Austria (1945–1955)

Former condominia

[edit]- Allied-occupied Germany and subsequently East Germany, West Germany, and West Berlin were under the control of the Allied Control Council, which consisted of representatives from France, the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom from 1945 until 1990.

- In 688 the Byzantine Emperor Justinian II and the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan reached an unprecedented agreement to establish a condominium (the concept did not yet exist) over Cyprus, with the collected taxes from the island being equally divided between the two parties. The arrangement lasted for some 300 years, even though in the same time there was nearly constant warfare between the two parties on the mainland.[76]

- Fellesdistrikt (Norwegian: Fellesdistrikt, Russian: Общий район) was a Russo-Norwegian condominium comprising Sør-Varanger Municipality and the Pechengsky District from 1684 until 1826.

- Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was legally an Egyptian-British condominium from 1899 until 1956, although in reality Egypt played no role in its government other than providing some administrators in the country: all political decisions were made by the United Kingdom and all Governors-General of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan were British. The system was resented by Egyptian and Sudanese nationalists, and would later be disavowed by the Egyptian Government, although it persisted due to the United Kingdom's effective control over Egypt itself, which began from 1882 and continued until at least 1936.

- The Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina was jointly ruled by Cisleithanian Austria and Transleithanian Hungary between 1908 and 1918, while both countries were parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

- An islet in the border river Brömsebäck was considered to belong to neither (or both) Denmark and Sweden.[citation needed]

- The Duchy of Courland was a condominium of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of Poland from 1726 until 1795.

- The Independent State of Croatia during World War II from 1941 to 1943 was a military condominium of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy until 1943, when Italy split between the Allied-leaning Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III and Axis-leaning Italian Social Republic under Benito Mussolini.[77][78][79][80]

- Canton and Enderbury Islands were a British–American condominium from 1939 until 1979 when they became part of Kiribati.

- Couto Misto was shared until 1864 between Spain and Portugal, even though in its final decades of existence it was de facto independent.

- Egypt from 1876 to 1882 was under France and the United Kingdom.[81]

- A small area (Hadf and surroundings) on the Arabian Peninsula, a part of Oman, at one time was jointly ruled with the Emirati member state of Ajman. The agreement defining the Hadf zone was signed in Salalah on 26 April 1960 by Sultan Said bin Taimur and in Ajman on 30 April 1960 by Shaikh Rashid bin Humaid Al Nuaimi III, ruler of Ajman.[82] This provided for some joint supervision in the zone by the ruler of Ajman and the shaikhs under the rule of Muscat. It allowed the Ajman ruler to continue collecting zakat (Islamic tax). The ruler of Ajman was, however, not to interfere in the affairs of the local people, the Bani Ka'ab (a branch of the Banu Kaab), which were the sole responsibility of shaikhs who were under Muscat rule. The agreement was later terminated.[83][citation needed]

- The Holy Roman Empire hosted numerous condominia within its boundaries. Many princes and especially Imperial knights and counts mortgaged partial ownership or rights within their lands to the Emperor, sometimes in perpetuity. Most of these were located in the Swabian Circle, close to the Emperor's personal domains in Further Austria. Some condominia were shared by lesser princes, especially in cases of inheritances held in common by branches of a princely line. Disputes over condominium contracts were submitted to the Imperial court at Wetzlar, or petitioned to the Emperor himself. Some cases within the Holy Roman Empire included the following:

- The City of Bergedorf was a condominium of the Imperial cities of Hamburg and Lübeck, and the terms were extended beyond the Holy Roman Empire's dissolution until 1868, when Lübeck sold its rights in Bergedorf to Hamburg.

- The City of Erfurt from 12th century until the Thirty Years' War was shared between the Archbishopric of Mainz and the Counts of Gleichen, the latter replaced by the city council in 1289 (Concordata Gebhardi), the Landgrave of Thuringia in 1327 and the House of Wettin in 1483 (Treaty of Weimar).

- The County of Friesland (West Frisia) was from 1165 to 1493 a joint condominium of the County of Holland and the Prince-Bishopric of Utrecht, then again until 25 October 1555 under Imperial administration.

- The Imperial village of Holzhausen was a partial condominium, two thirds of which was immediate to the Emperor and the remaining third subject to various landlords.

- The City of Maastricht was a condominium for five centuries until 1794. It was shared between the Prince-Bishopric of Liège and the Duchy of Brabant, the latter replaced by the Dutch Republic in 1632.

- The village of Nennig was a condominium of the Trier bishopric, Lorraine (the Kingdom of France from 1766) and Duchy of Luxembourg until its annexation by Revolutionary France in 1794.

- The County of Sponheim was ruled since the 15th century by the Margraves of Baden, the Counts Palatine of the Rhine and the Counts of Veldenz, later Palatinate-Simmern, Palatine Zweibrücken and Palatinate-Birkenfeld as heirs of Veldenz.

- The Free City of Kraków was a protectorate of Prussia, Austria and Russia from 1815 until 1846, when it was annexed by Austria.

- Neutral Moresnet was shared from 1816 until 1919 between the Netherlands (later Belgium) and Prussia.

1966 flag of the colonial New Hebrides - Nauru was a tripartite condominium mandate territory administered by Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom from 1923 to 1942 and again in 1947 as a UN trust territory until independence in 1968.

- New Hebrides formed a French–British condominium in 1906 until independence in 1980 as a republic, now called Vanuatu.

- Northern Dobruja was shared by the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria) during World War I.[84]

- The Oregon Country was an Anglo-American condominium from 1818 until 1846. It would later become the Pacific Northwest of the United States and British Columbia in Canada.

- Samoan Islands from 1889 to 1899 were a rare tripartite condominium under joint protectorate of Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. It would later become Samoa and American Samoa.

- Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg were an Austrian-Prussian condominium. The two German powers acceded it following the 1864 Second Schleswig War. According to the Gastein Convention in the next year, Lauenburg left the condominium (to Prussia), Austria governed Holstein and Prussia controlled Schleswig. In 1866, after the Austro-Prussian War, Austria passed over its remaining rights to Prussia. Prussia later created the Province of Schleswig-Holstein, which would become divided between Germany and Denmark after the Treaty of Versailles.

- The Spanish Netherlands became an Anglo-Dutch condominium in 1706 during the War of the Spanish Succession, until the peace treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt in 1713/14 ending the war.[85]

- Togoland, formerly a German protectorate, was an Anglo-French condominium, from when the United Kingdom and France occupied it on 26 August 1914 until its partition on 27 December 1916 into French and British zones. The divided Togoland became two separate League of Nations mandates on 20 July 1922: British Togoland, which joined Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) in 1956, and French Togoland, which is now the nation of Togo.

- Zaporozhian Sich, a brief condominium between Russia and Poland-Lithuania, was established in 1667 by the Treaty of Andrusovo.

- Tangier International Zone, an international zone nominally under Moroccan sovereignty but jointly administered by several European powers in 1924. It was returned to full Moroccan sovereignty in 1956.

- The term is sometimes even applied to a similar arrangement between members of a Monarch's countries in (personal or formal) union, as was the case for the district of Fiume (what is today Rijeka, Republic of Croatia), shared between Hungary and Croatia within the Habsburg Empire since 1868.

- Between 1913 and 1920 Spitsbergen was a neutral condominium. The Spitsbergen Treaty of 9 February 1920 recognises the full and absolute sovereignty of Norway over all the arctic archipelago of Svalbard. The exercise of sovereignty is, however, subject to certain stipulations, and not all Norwegian law applies. Originally limited to nine signatory nations, over 40 are now signatories of the treaty. Citizens of any of the signatory countries may settle in the archipelago. Currently, only Norway and Russia make use of this right.

- In 1992, South Africa and Namibia established a Joint Administrative Authority in the enclave of Walvis Bay, prior to its cession to Namibia in 1994.[86]

- The Saudi Arabian–Kuwaiti neutral zone was established in 1922 by the Uqair Convention. It was a 2,000 square mile area designed to accommodate the Bedouin people, a nomadic group who regularly crossed through the Saudi and Kuwaiti border. The area was partitioned in 1970 after a 1938 discovery of oil near the zone brought speculation that there may be oil in the condominium.

See also

[edit]- History of Africa#1951 – present

- Postcolonial Africa

- Economic history of Africa

- List of European colonies in Africa

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Africa

- States and Power in Africa

- Africa–United States relations

- Wars of national liberation

- decolonisation of Africa

- Year of Africa

- British Protected Person

- Client state

- European Union Police Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- EUFOR Althea

- High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina

- League of Nations mandate

- Peace Implementation Council

- Protector (titles for Heads of State and other individual persons)

- Protectorate (imperial China)

- Timeline of national independence

- Tribute

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hoffmann, Protectorates (1987), p. 336.

- ^ a b c Fuess, Albrecht (1 January 2005). "Was Cyprus a Mamluk protectorate? Mamluk policies toward Cyprus between 1426 and 1517". Journal of Cyprus Studies. 11 (28–29): 11–29. ISSN 1303-2925. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Reisman, W. (1 January 1989). "Reflections on State Responsibility for Violations of Explicit Protectorate, Mandate, and Trusteeship Obligations". Michigan Journal of International Law. 10 (1): 231–240. ISSN 1052-2867. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Bojkov, Victor D. "Democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Post-1995 political system and its functioning" (PDF). Southeast European Politics 4.1: 41–67.

- ^ Leys, Colin (2014). "The British ruling class". Socialist Register. 50. ISSN 0081-0606. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Kirkwood, Patrick M. (21 July 2016). ""Lord Cromer's Shadow": Political Anglo-Saxonism and the Egyptian Protectorate as a Model in the American Philippines". Journal of World History. 27 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1353/jwh.2016.0085. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 148316956. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Rubenson, Sven (1966). "Professor Giglio, Antonelli and Article XVII of the Treaty of Wichale". The Journal of African History. 7 (3): 445–457. doi:10.1017/S0021853700006526. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180113. S2CID 162713931. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Archer, Francis Bisset (1967). The Gambia Colony and Protectorate: An Official Handbook. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-1139-6.

- ^ Johnston, Alex. (1905). "The Colonization of British East Africa". Journal of the Royal African Society. 5 (17): 28–37. ISSN 0368-4016. JSTOR 715150. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b Meijknecht, Towards International Personality (2001), p. 42.

- ^ Willigen, Peacebuilding and International Administration (2013), p. 16.

- ^ Yoon, Jong-pil (17 August 2020). "Establishing expansion as a legal right: an analysis of French colonial discourse surrounding protectorate treaties". History of European Ideas. 46 (6): 811–826. doi:10.1080/01916599.2020.1722725. ISSN 0191-6599. S2CID 214425740. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Willigen, Peacebuilding and International Administration (2013), p. 16: "First, protected states are entities which still have substantial authority in their internal affairs, retain some control over their foreign policy, and establish their relation to the protecting state on a treaty or another legal instrument. Protected states still have qualifications of statehood."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Onley, The Raj Reconsidered (2009), p. 50.

- ^ Willigen, Peacebuilding and International Administration (2013), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Onah, Emmanuel Ikechi (9 January 2020). "Nigeria: A Country Profile". Journal of International Studies. 10: 151–162. doi:10.32890/jis.10.2014.7954. ISSN 2289-666X. S2CID 226175755. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Moloney, Alfred (1890). "Notes on Yoruba and the Colony and Protectorate of Lagos, West Africa". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. 12 (10): 596–614. doi:10.2307/1801424. ISSN 0266-626X. JSTOR 1801424. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Wick, Alexis (2016), The Red Sea: In Search of Lost Space, Univ of California Press, pp. 133–, ISBN 978-0-520-28592-7

- ^ Αλιβιζάτου, Αικατερίνη (12 March 2019). "Use of GIS in analyzing archaeological sites: the case study of Mycenaean Cephalonia, Greece". University of Peloponnese. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Dumieński, Zbigniew (2014). Microstates as Modern Protected States: Towards a New Definition of Micro-Statehood (PDF) (Report). Occasional Paper. Centre for Small State Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Cunningham, Joseph Davy (1849). A History of the Sikhs: From the Origin of the Nation to the Battles of the Sutlej. John Murray.

- ^ Meyer, William Stevenson (1908). "Ferozepur district". The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. XII. p. 90.

But the British Government, established at Delhi since 1803, intervened with an offer of protection to all the CIS-SUTLEJ STATES; and Dhanna Singh gladly availed himself of the promised aid, being one of the first chieftains to accept British protection and control.

- ^ Mullard, Saul (2011), Opening the Hidden Land: State Formation and the Construction of Sikkimese History, BRILL, p. 184, ISBN 978-90-04-20895-7

- ^ a b "Timeline – Story of Independence". Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ Francis Carey Owtram (1999). "Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920" (PDF). University of London. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Onley, The Raj Reconsidered (2009), pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Onley, The Raj Reconsidered (2009), p. 51.

- ^ "A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, by Michael J. Seth", p112

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (April 1995), Tibet, China and the United States (PDF), The Atlantic Council, p. 3 – via Case Western Reserve University

- ^ Norbu, Dawa (2001), China's Tibet Policy, Routledge, p. 78, ISBN 978-1-136-79793-4

- ^ Lin, Hsaio-ting (2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928–49. UBC Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7748-5988-2.

- ^ Sloane, Robert D. (Spring 2002), "The Changing Face of Recognition in International Law: A Case Study of Tibet", Emory International Law Review, 16 (1), note 93, p. 135: "This ["priest-patron"] relationship reemerged during China's prolonged domination by the Manchu Ch'ing dynasty (1611–1911)." – via Hein Online

- ^ Karan, P. P. (2015), "Suppression of Tibetan Religious Heritage", in S. D. Brunn (ed.), The Changing World Religion Map, Spriger Science, p. 462, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9376-6_23, ISBN 978-94-017-9375-9

- ^ Sinha, Nirmal C. (May 1964), "Historical Status of Tibet" (PDF), Bulletin of Tibetology, 1 (1): 27

- ^ "Indonesian traditional polities". rulers.org. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ "Indonesian Traditional States part 1". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ "Indonesian Traditional States Part 2". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ^ See the classic account on this in Robert Delavignette. Freedom and Authority in French West Africa. London: Oxford University Press, (1950). The more recent standard studies on French expansion include:

Robert Aldrich. Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion. Palgrave MacMillan (1996) ISBN 0-312-16000-3.

Alice L. Conklin. A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa 1895–1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press (1998), ISBN 978-0-8047-2999-4.

Patrick Manning. Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, 1880–1995. Cambridge University Press (1998) ISBN 0-521-64255-8.

Jean Suret-Canale. Afrique Noire: l'Ere Coloniale (Editions Sociales, Paris, 1971); Eng. translation, French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900 1945. (New York, 1971). - ^ Bedjaoui, Mohammed (1 January 1991). International Law: Achievements and Prospects. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9231027166 – via Google Books.

- ^ Capaldo, Giuliana Ziccardi (1 January 1995). Repertory of Decisions of the International Court of Justice (1947–1992). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0792329937 – via Google Books.

- ^ C. W. Newbury. Aspects of French Policy in the Pacific, 1853–1906. The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1958), pp. 45–56

- ^ Gonschor, Lorenz Rudolf (August 2008). Law as a Tool of Oppression and Liberation: Institutional Histories and Perspectives on Political Independence in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti Nui/French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (Thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. pp. 56–59. hdl:10125/20375.

- ^ a b Gründer, Horst (2004). Geschichte der deutschen Kolonien (in German). Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-8252-1332-9.

- ^ Hoffmann, Protectorates (1987), pp. 336–339.

- ^ Cunningham, Joseph Davy (1849). A History of the Sikhs: From the Origin of the Nation to the Battles of the Sutlej. John Murray.

- ^ Meyer, William Stevenson (1908). "Ferozepur district". The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. XII. p. 90.

But the British Government, established at Delhi since 1803, intervened with an offer of protection to all the CIS-SUTLEJ STATES; and Dhanna Singh gladly availed himself of the promised aid, being one of the first chieftains to accept British protection and control.

- ^ Mullard, Saul (2011), Opening the Hidden Land: State Formation and the Construction of Sikkimese History, BRILL, p. 184, ISBN 978-90-04-20895-7

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Fascism European Empire.

- ^ Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale p. 49

- ^ a b Gerrits, Andre W. M.; Bader, Max (2 July 2016). "Russian patronage over Abkhazia and South Ossetia: implications for conflict resolution". East European Politics. 32 (3): 297–313. doi:10.1080/21599165.2016.1166104. hdl:1887/73992. ISSN 2159-9165. S2CID 156061334.

- ^ Pieńkowski, Jakub (2016). "Renewal of Negotiations on Resolving the Transnistria Conflict". Central and Eastern European Online Library (CEEOL). Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Greene, Sam (26 April 2019). "Putin's 'Passportization' Move Aimed At Keeping the Donbass Conflict on Moscow's Terms". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Paul (1 October 2016). "Russia's role in the war in Donbass, and the threat to European security". European Politics and Society. 17 (4): 506–521. doi:10.1080/23745118.2016.1154229. ISSN 2374-5118. S2CID 155529950.

- ^ "Putin's Karabakh victory sparks alarm in Ukraine". Atlantic Council. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Goble, Paul (25 November 2020). "Nagorno-Karabakh Now A Russian Protectorate – OpEd". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 21 September 2021.