STS-71

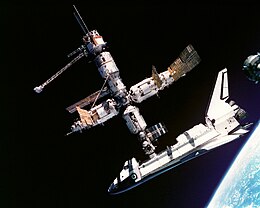

Atlantis docked to Mir, photographed from the departing Soyuz-TM spacecraft Uragan | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-71 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Shuttle-Mir |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1995-030A |

| SATCAT no. | 23600 |

| Mission duration | 9 days, 19 hours, 23 minutes, 9 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 6,600,000 kilometres (4,100,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 153 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Payload mass | 12,191 kilograms (26,877 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 up 8 down |

| Members | |

| Launching | |

| Landing | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | June 27, 1995, 19:32:19 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | July 7, 1995, 14:55:28 UTC |

| Landing site | Kennedy, SLF Runway 15 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 342 kilometres (213 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 342 kilometres (213 mi) |

| Inclination | 51.6 degrees |

| Period | 88.9 min |

| Docking with Mir | |

| Docking port | Kristall forward |

| Docking date | June 29, 1995, 13:00:16 UTC |

| Undocking date | July 4, 1995, 11:09:42 UTC |

| Time docked | 4 days, 22 hours, 9 minutes 26 seconds |

Left to right – Seated: Dezhurov, Gibson, Solovyev; Standing: Thagard, Strekalov, Harbaugh, Baker, Precourt, Dunbar, Budarin | |

As the third mission of the US/Russian Shuttle-Mir Program, STS-71 became the first Space Shuttle to dock with the Russian space station Mir. STS-71 began on June 27, 1995, with the launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis from launchpad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Shuttle delivered a relief crew of two cosmonauts Anatoly Solovyev and Nikolai Budarin to the station and recovered Increment astronaut Norman Thagard. Atlantis returned to Earth on July 7 with a crew of eight. It was the first of seven straight missions to Mir flown by Atlantis, and the second Shuttle mission to land with an eight-person crew after STS-61-A in 1985.

For the five days the Shuttle was docked to Mir they were the largest spacecraft in orbit at the time. STS-71 marked the first docking of a Space Shuttle to a space station, the first time a Shuttle crew switched members with the crew of a station, and the 100th crewed space launch by the United States. The mission carried Spacelab and included a logistical resupply of Mir. Together the Shuttle and station crews conducted various on-orbit joint US/Russian life science investigations with Spacelab along with the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment-II (SAREX-II) experiment.

Crew

[edit]| Position | Launching Crew Member | Landing Crew Member |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Fifth and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Third and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 Flight Engineer |

Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Fourth spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | EO-19 Fourth spaceflight |

EO-18 Fifth and last spaceflight |

| Mission Specialist 5 | EO-19 First spaceflight |

EO-18 First spaceflight |

| Mission Specialist 6 | None | EO-18 Fifth and last spaceflight |

Crew seat assignments

[edit]| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the flight deck. Seats 5–8 are on the mid-deck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gibson | ||

| 2 | Precourt | ||

| 3 | Baker | ||

| 4 | Harbaugh | ||

| 5 | Dunbar | ||

| 6 | Solovyev | Strekalov | |

| 7 | Budarin | Dezhurov | |

| 8 | Thagard | ||

Mission highlights

[edit]

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 Jun 1995, 5:09:00 pm | Scrubbed | — | Weather | 23 Jun 1995, 10:00 am (T−06:25:00) | Lightning was within five miles of the KSC area, prohibiting tanking operations.[2][3] | |

| 2 | 25 Jun 1995, 4:43:00 pm | Scrubbed | 1 day 23 hours 34 minutes | Weather | 25 Jun 1995, 4:00 pm (T−00:09:00 hold) | Thunderstorms and rain were in the KSC area.[4] | |

| 3 | 27 Jun 1995, 3:32:19 pm | Success | 1 day 22 hours 49 minutes |

The primary objectives of this flight were to rendezvous and perform the first docking between the Space Shuttle and the Russian Space Station Mir on June 29. In the first U.S.-Russian (Soviet) docking in twenty years, Atlantis delivered a relief crew of two cosmonauts Anatoly Solovyev and Nikolai Budarin to Mir.[5]

Other prime objectives were on-orbit joint United States of America-Russian life sciences investigations aboard SPACELAB/Mir, logistical resupply of the Mir and recovery of US astronaut Norman E. Thagard.[3]

Secondary objectives included filming with the IMAX camera and the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment-II (SAREX-II) experiment.[5]

STS-71 was the 100th U.S. human space launch conducted from Cape Canaveral, the first U.S. Space Shuttle-Russian Space Station docking and joint on-orbit operations; largest spacecraft ever in orbit; and the first on-orbit changeout of Shuttle crew.

The rendezvous sequence began at 15:32:19 EDT with a lift-off in-plane with Mir's orbit, at the opening of the 10 minute 19 second launch window. Ascent was nominal with no OMS 1 burn required.[5] The OMS 2 burn, initiated at 42 minutes 58 seconds Mission Elapsed Time, adjusted the orbit to 160 x 85.3 nautical miles. It was the lowest ever perigee altitude flown by an orbiter.[6]: 3 This facilitated a very rapid initial catch up rate with Mir of about 880 nautical miles per orbit.[7] Almost three hours later the orbit was raised to more typical values of 210 x 159 nautical miles by the OMS 3 burn.

Docking occurred at 9 am EDT, June 29, using R-Bar or Earth radius vector approach, with Atlantis closing in on Mir from directly below. R-bar approach allows natural forces to brake the orbiter's approach more than would occur along standard approach directly in front of the space station; also, an R-bar approach minimizes the number of orbiter jet firings needed for approach. The manual phase of the docking began with Atlantis about a half-mile (800 m) below Mir, with Gibson at the controls on aft flight deck. Stationkeeping was performed when the orbiter was about 75 meters (246 ft) from Mir, pending approval from Russian and U.S. flight directors to proceed. Gibson then maneuvered the orbiter to a point about 10 meters (33 ft) from Mir before beginning the final approach to station. Closing rate was close to the targeted 0.1 foot per second (30 mm/s), being approximately 0.107 foot per second (33 mm/s) at contact. Interface contact was nearly flawless: less than 25 millimeters (0.98 in) lateral misalignment and an angular misalignment of less than 0.5 degrees per axis. No braking jet firings had been required.[6]: 3 Docking occurred about 216 nautical miles (400 kilometers (250 mi)) above Lake Baikal region of the Russian Federation. The Orbiter Docking System (ODS) with Androgynous Peripheral Docking System served as the actual connection point to a similar interface on the docking port on Mir's Kristall module. ODS, located in the forward payload bay of Atlantis, performed flawlessly during the docking sequence.

When linked, Atlantis and Mir formed the largest spacecraft ever in orbit, with a total mass of about 225 metric tons (almost one-half million pounds), orbiting some 218 nautical miles (404 kilometers (251 mi)) above the Earth. After hatches on each side opened, STS-71 crew passed into Mir for a welcoming ceremony. On the same day, the Mir 18 crew officially transferred responsibility for the station to the Mir 19 crew, and the two crews switched spacecraft.

For the next five days, about 100 hours in total, joint U.S.-Russian operations were conducted, including biomedical investigations, and transfer of equipment to and from Mir. Fifteen separate biomedical and scientific investigations were conducted, using the Spacelab module installed in the aft portion of Atlantis's payload bay, and covering seven different disciplines: cardiovascular and pulmonary functions; human metabolism; neuroscience; hygiene, sanitation and radiation; behavioral performance and biology; fundamental biology; and microgravity research. The Mir 18 crew served as test subjects for investigations. Three Mir 18 crew members also carried out an intensive programme of exercise and other measures to prepare for re-entry into gravity environment after more than three months in space.

Numerous medical samples as well as disks and cassettes were transferred to Atlantis from Mir, including more than 100 urine and saliva samples, about 30 blood samples, 20 surface samples, 12 air samples, several water samples and numerous breath samples taken from Mir 18 crew members. Also moved was a broken Salyut-5 computer. Transferred to Mir were more than 450 kilograms (990 lb) of water generated by the orbiter for waste system flushing and electrolysis; specially designed spacewalking tools for use by the Mir 19 crew during a spacewalk to repair a jammed solar array on the Spektr module; and transfer of oxygen and nitrogen from Shuttle's environmental control system to raise air pressure on the station, to improve Mir's consumables margin.

The spacecraft undocked on July 4, following a farewell ceremony, with the Mir hatch closing at 3:32 pm EDT. July 3 and hatch on Orbiter Docking System shut 16 minutes later. Gibson compared separation sequence to a "cosmic" ballet: Prior to the Mir-Atlantis undocking, the Mir 19 crew temporarily abandoned station, flying away from it in their Soyuz spacecraft so they could record images of Atlantis and Mir separating. Soyuz unlatched at 6:55 am EDT, and Gibson undocked Atlantis from Mir at 7:10 am EDT. Whilst both spacecraft were undocked from Mir, the station suffered a computer malfunction and started to drift in attitude. The Mir 19 crew performed a hasty re-docking, monitored by Atlantis. They subsequently replaced computer hardware allowing them to regain attitude control.

The returning crew of eight equaled the largest crew (STS-61-A, October 1985) in Shuttle history. To ease their re-entry into gravity environment after more than 100 days in space, Mir 18 crew members Thagard, Dezhurov and Strekalov lay supine in custom-made recumbent seats installed prior to landing in the orbiter middeck.

Inflight problems included a glitch with General Purpose Computer 4 (GPC 4), which was declared failed when it did not synchronize with GPC 1; subsequent troubleshooting indicated it was an isolated event, and GPC 4 operated satisfactorily for the remainder of mission.

During the SAREX portion of the flight, the crew contacted several schools. One was Redlands High School in Redlands, California. Charlie Precourt was able to contact students, former students and technicians that built the communications package. A cross polarized, dual band yagi antenna array and automatic rotor was installed on the roof of the electronics classroom. A dual band radio was installed inside the radio room of the classroom. The contact window lasted about 10 minutes, during which time, about twelve people were able to ask questions. While most were basic or technical questions, one was peculiar. "What would happen of you sneezed inside your helmet?" Precourt answered that you'd probably, "spray your face shield a little bit.." and carry on.

External tank

[edit]The external tank used on this mission (ET-70)[6] was involved in a historic marine salvage court case.[8] The tank was being delivered by barge in November 1994, when the tow vehicle encountered issues in Hurricane Gordon. Their mayday signal was picked up by the oil tanker Cherry Valley, which responded and towed the tug and its cargo to safety.[9] Under the tradition of marine salvage, NASA offered $5 million to the crew of the tanker as a reward, but the United States Department of Justice reduced the offer to $1 million.[9] The tanker company and crew sued and were awarded $6.4 million, believed to be the largest such award in U.S. history.[9] This was reduced to $4.125 million on appeal.[8] The crew split the award with their employer. At least one crew member was able to use his cut of the proceeds to buy a house, which he calls "the house that NASA bought."[9]

See also

[edit]- List of human spaceflights

- List of human spaceflights to Mir

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Outline of space science

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame#Exhibits

References

[edit]- ^ "STS-71". Spacefacts. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Brown, Irene (June 23, 1995). "Weather scrubs shuttle launch". UPI. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Legler, Robert D.; Bennett, Floyd V. (September 1, 2011). "Space Shuttle Missions Summary" (PDF). Scientific and Technical Information (STI) Program Office. NASA. pp. 83–84. NASA/TM–2011–216142. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ballingrud, David (June 25, 1995). "Atlantis' launch off; will try again Tuesday". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates public domain material from Dumoulin, Jim. STS-71 (69). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (June 29, 2001).

This article incorporates public domain material from Dumoulin, Jim. STS-71 (69). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (June 29, 2001).

- ^ a b c Fricke Jr., Robert W. (August 1995). "STS-71 Space Shuttle Mission Report" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ "STS-71 Day 1 Highlights". NASA. 1995.

- ^ a b Margate Shipping Co. v. M/V JA Orgeron, US 143 F.3d 976 (5th Cir. 1998) (July 1, 1998).

- ^ a b c d "Rescues at sea, and how to make a fortune". Planet Money. NPR. January 26, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

External links

[edit]- STS-71 Video Highlights Archived November 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine